Jonny died of AIDS on February 19, 1999

Jonny was a member of ASGRA

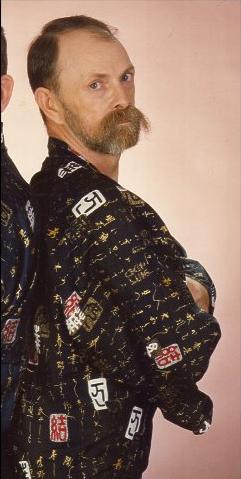

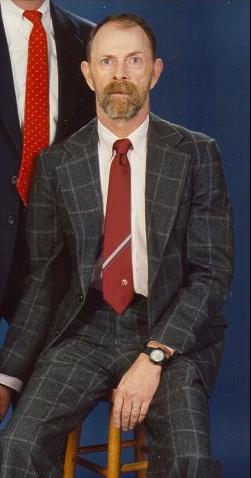

Jonny Charles Dodgen

(Jonda)

Written by Eric, Johny's partner

Johnny Dodgen, a Washington, DC-area resident since 1983, died on February 19, 1999 of complications due to AIDS. He was 54 years old.Born in Knoxville, Tennessee and raised in several East Tennessee communities, Johnny joined the US Navy after graduating from high school in Knoxville. He served on the USS Cone and was stationed in the Mediterranean. He traveled widely throughout Europe and South Asia during his service. After discharge, Johnny returned to Knoxville, where he studied business management at the Cooper Institute of Business. Through the 1960s and 1970s he owned and managed several pet wholesale and retail businesses before coming to the Washington area. In the Washington area, he worked most recently at Rags to Riches, an Alexandria pet grooming shop that he managed until he retired for health reasons in 1997.

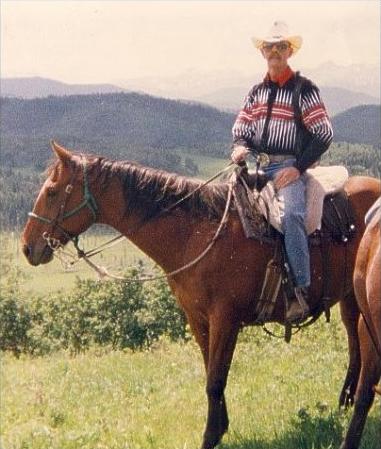

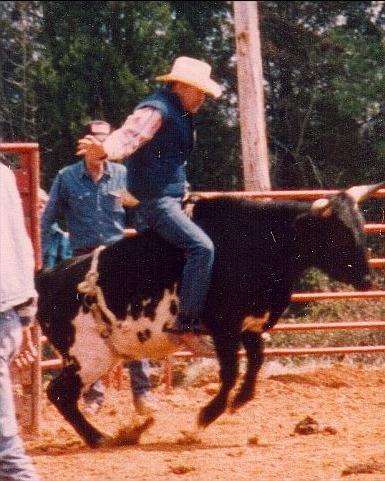

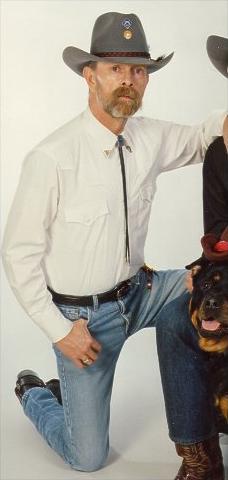

Johnny was devoted to the breeding, care and grooming of animals, both professionally and as his avocation. He was an avid horseman and a member of the Atlantic States Gay Rodeo Association. He was a rodeo enthusiast and was a certified rodeo judge for the International Gay Rodeo Association. He lived on a farm in Aquasco, MD with his lifetime companion, Eric, where the two raised horses and ducks, as well as their pet dogs and cat. He enjoyed gardening and caring for his orchid collection.

"Johnny was a person of very strong determination. Once he'd made up his mind, he would stop at nothing to carry out his will. He was devoted to his friends, and he considered all beings to be his friends, once a bond had been established. He had a sly sense of humor and was always able to find a way to help others feel at ease with a joke. He cared very deeply about their wellbeing and expressed his care by hands-on treatment and love," said Eric. Jonny was deeply spiritual and continued to seek after the tradition of his grandfather, a Native American from the Smokey Mountains.

In addition to his partner, Johnny was survived by his stepmother, Helen, his sister, Tona, his brothers, Chuck and Buddy, all of Morristown, Tennessee, his nephew, Jason, of Bean Station, Tennessee, and his daughter, Lisa, of Sykesville, Maryland. He was predeceased by his father Ulys J. His remains were cremated and scattered near his grandparents' burial site at Gatlinburg, TN.

Rodeo Involvement

(This section added March, 2013)

Johnny had been involved in the care and maintenance of horses from his childhood in east Tennessee. He moved to the Washington DC area in 1983 and soon began working in local pet store and grooming businesses, ultimately owning his own pet store - George's - in Bladensburg, Maryland. Johnny joined ASGRA in 1992, a year after it was founded. He enjoyed hanging out with ASGRA members at its then home bar - Wild Oats - in Southeast DC. He did volunteer work for Atlantic Stampede in 1993 and competed at Atlantic Stampede in 1994, when it was held at the Anne Arundel County Fairgrounds. He competed in barrels, poles and flag race.

At the time, Johnny competed on a horse that he'd borrowed from a friend to ride in the rodeo, but soon after, he bought Sunny, an Appaloosa that he boarded at Piscataway Stables, south of Washington, in Clinton, MD. Almost all ASGRA members at the time who owned horses were boarding them there. It was also the site of the monthly ASGRA trial ride and continues to be so today.

Johnny's interest in rodeo continued to deepen. He attended the IGRA convention at Omaha, NE with me, Gary Robinson and others from ASGRA and immediately gravitated to the Rules Committee. He attended the next two IGRA conventions as well, continuing to represent ASGRA on the Rules Committee. At the same time, he took up interest in judging and began the process of training as an IGRA-certified rodeo judge, He did his field work at rodeos across the country. I particularly remember our attending the GSGRA rodeo at the Cow Palace in San Francisco, where he did his last round of field work even though he was feeling pretty poor. (When he got back home, he was hospitalized for pneumonia and dehydration and stayed in the hospital for about a week.) He was certified as one of ASGRA's first certified judges, together with Mike Lentz.

Johnny loved the country life style. He loved two-stepping and line dancing at Wild Oats and at the Equus, the predecessor to Remington's, in Washington. He spent as much time as he could with his horses - first, Sunny the Appaloosa, and later with Lieta and Chani (he was a Dunes movie fan), a mare and her foal that he bought in 1997. He loved working with them so much that he wanted to live on a farm where he could keep them - not board them out at a stables. He convinced me to move out from the city, and finally in 1998, we did move to our farm in southern Maryland, where he kept all his horses - only a sad six months before he died of AIDS.

He loved working on rodeos and going to them. One of his all-time favorite memories was of going out with a large crew of people from DC to the Illinois association and helping them set up and operate a successful first-time rodeo.

When Jonny and Eric Met

(The rest of this document was written around 2000)

Johnny and Eric first met on a sunny Saturday afternoon in September, 1978 at the Chilhowie Park flea market in Knoxville, TN. It was right down the hill from Eric's home.

Johnny and Eric first met on a sunny Saturday afternoon in September, 1978 at the Chilhowie Park flea market in Knoxville, TN. It was right down the hill from Eric's home.

Johnny was selling Doberman puppies. Eric saw the stall and was curious. He was a cat person and felt more than a little intimidated by Dobermans, but he was attracted to Johnny. Eric had come with a young friend who wanted to browse around the stalls. Eric let his friend to himself and wandered back to the Doberman stall.

Johnny had noticed Eric and wished he'd come back, but flea markets were flea markets, and people come and go. Someone else as attractive might come by today, he thought, but doubted it. Then he saw Eric making his way back through the crowd and flashed a smile.

Eric immediately came over but stood by awkwardly. Johnny tried his usual opening line: "Haven't I seen you here before?" Eric, a novice at flirting, stumbled through an explanation that he was teaching at the local university and doubted that he'd met Johnny before unless he'd been taking first-year Japanese, which he was teaching, but he doubted it, because after all, he'd have remembered anyone taking language in his class, but Johnny didn't look familiar, etc., etc.

Johnny just flashed another smile and took him by the sleeve to look at a pup. Eric finally began to warm up, and they struck up a conversation that lasted until his young friend came by complaining that he was being ignored. Eric left with him. His only regret as he walked away was that Johnny was straight. Johnny was under no such illusion about Eric. Johnny's only regret was that he hadn't gotten Eric's phone number.

Johnny continued to look around Knoxville for Eric but didn't see him again until the night of October 15. He had gone to the Carousel, one of several Knoxville gay bars. Johnny was in the final stages of a failing relationship with his roommate and sometimes lover who, for his part, had been happy enough to see him leave for the evening. He had his own plans. Once Johnny got to the bar, little was happening, and he sat at the bar for a beer.

Later in the evening, Eric came in, unaccompanied this time by the young boyfriend who'd been with him at the flea market. Said boyfriend in fact had dumped Eric on his birthday the week before. Eric was happy enough for that fact and was celebrating a late birthday that night.

It was Sunday night. The next day was a workday, and Knoxville lived by the book of work. So did Eric. On this night, for whatever reason, the crowd stayed on late, and Eric stayed on with it. He continued to move around the floor talking with various men, but no one in particular. He didn't see Johnny, who kept hidden in the shadows. Johnny for his part was too shy to say hello to strangers in a bar, where he didn't have his dogs for a cover.

Around 11 PM, a young bartender from another of the local gay bars came up to Eric and said there was someone he wanted to introduce to him. In fact, Johnny had set him up and told Eric so long, long afterwards. The bartender took him up to the bar, and there was Johnny. Laughing, he introduced the two and went back out on the floor.

Eric sat down on a barstool next to Johnny. Once again, the conversation wasn't getting too far. Eric for his part kept slipping back into professorial mode, and Johnny remained stubbornly silent. They strained to find some common thread. Finally, Eric did something unusual. He acted. He took Johnny's hand and shoved it down in his crotch as they sat next to each other.

They didn't need to do anything more. A jolt went between them, a flood of energy and ecstasy. They never questioned it but let it do its work. They forgot time, for that night and for a long time afterwards.

Throughout their time together, Johnny and Eric referred to sex as having an intelligent conversation.

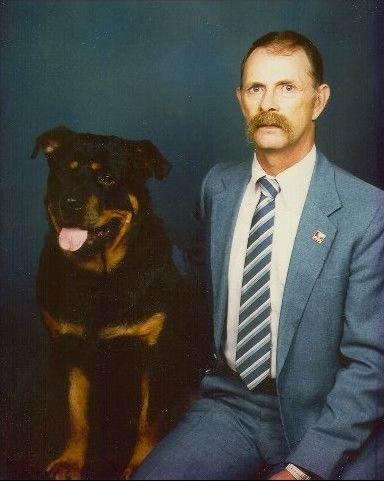

Bear

Bear was a Rottweiler. He was Johnny's best dog. Johnny loved Bear very much. Bear died in August, 1998, several months before Johnny himself died. He never overcame his grief for that dog.

Bear was a Rottweiler. He was Johnny's best dog. Johnny loved Bear very much. Bear died in August, 1998, several months before Johnny himself died. He never overcame his grief for that dog.

Johnny got Bear in 1988, when Bear was just about a year old. He had been passed among several owners, none of whom had given him a good home. The previous owner, a young man with little sense of how to raise a Rotty, attempted to dognap Bear back. Johnny argued and threatened legal action, since he'd paid him good money for Bear. His papers were all in order, and dognapping was a legal offense. In the end, however, Johnny got Bear back, and nothing came of the threats.

Eric for his part was nonplussed. He'd always been a cat person. Nothing had changed since the Knoxville days, and an animal of this size was overwhelming. The Dobermans in Knoxville at least had been kept at arm's length. This time, the dog was thrown in on top of the two in a cramped apartment. At the time, they were living in a rental unit, having recently returned from an extended tour of duty abroad, given Eric's work. The apartment unit would not allow pets, and so they had to keep him hidden while they began the work of looking for their own home. Pretending that a Rotty is invisible while doing his thing out behind the landscaped bushes is hard work, but they managed to carry it off and moved to their first home about two months later, in February, 1989.

Bear had been the runt of the litter. (In a Rotty, that's hard to tell.) He also had curly hair. His lineage was German, his siblings were prizewinners, but Bear was not going to be a show dog. He was just going to be a dog. None of this mattered to Eric, though. For months he was afraid to let Bear approach him, with his oversized teeth, massive jaws, barrel chest and boundless energy.

Johnny changed that. Under his love, care and training, Bear became a prince. He was extremely well behaved and gentle. Eric gradually learned to let Bear take his wrist in his teeth, and then to kneel down on the carpet and let Bear embrace him with his front paws, and finally just to roll around with Bear on the floor, each trying to outwrestle the other. The kids in the neighborhood loved to come by to take him for walks. Mrs. Johnson next door always had a treat for him. He made everyone feel safe. He tolerated K.T., Eric's finicky cat, with infinite grace.

Two years later, in a generous gesture, the owner of Rags to Riches gave Johnny a second Rottweiler - a young female to keep Bear company. Eric went ballistic. One dog was enough on their hands. Two meant that much more work cleaning up the yard. Besides, she was totally untrained and was chewing up every shoe in sight. He refused to speak to Johnny for days. Clearly, something had to be done. Thus began Johnny's training of Eric in the world of animals.

The first thing Johnny did was to assign Eric the job of finding the female pup a name. (Eric, of course, had relented after a few days of his normal petulance.) Johnny could name anything - animals, plants, rocks, cars, people, medicines - to make them his and thought the same technique might work with Eric. Eric took on the job but hated it. He'd never been any good at names. That was just one more thing he'd depended on Johnny for.

Bear had been registered with the AKA as "Kuma Inu" at Johnny's insistence. That was merely "Bear Dog," in Japanese, but it sounded exotic. Eric thought and thought. Here presumably was the world's prettiest little consort for a regal Japanese prince, and the name finally came to him - Murasaki Shikibu, consort to the legendary Prince Genji of Japan. So they registered her. After some experimentation and stumbling, the whole world - Johnny, Eric and the neighbors - came to know her simply as Shiki.

Eric slowly entered Johnny's world. There had always been the cat, but now there two dogs - big dogs. From the cat and dogs sprang forth Cody, a leased horse. And when Cody was put out to pasture, there was Washi-Sunny, the palomino they owned with pride. And from Sunny came Bismarck, the Appaloosa that their friend Gary had left behind when he died of AIDS. Bismarck left, and in his place came Lie Tawah, known as Lieta, a spooky mare that could turn the barrels on a dime. Then, totally unexpectedly, just after they bought Lieta from the Edelman boys, she gave birth to a little filly named Chani. No one, especially the Edelman boys, had realized she was pregnant. She was, they said later, a two fer.

There had been many dogs in Knoxville, but there had been birds and fish, too. When Johnny got Bear, he also inherited Kukla, a scarlet macaw with a foul mouth and a personality to match. Now here in Washington, there first came the peacocks and guinea hens, kept at the tack room together with the horses. There was Bud the rooster, a runty little thing with a bacterial disease that prevented it from walking upright. "Too much Budweiser in that cock," observed Johnny. Then came the quail, dozens of them hatched off at home in styrofoam incubators and released back into the park along the Anacostia. There were ducks and chicks hatched along with them and kept at the stables. Johnny had hatched each one off and imprinted himself on it. The flock would come running up to his red truck every morning when he went out to feed the horses. The ducks would gather around, noisily demanding breakfast.

Johnny loved and cared for and thought about all these animals. He had a deep bond with them. They were far more trustworthy, he thought, than most people. And through him, Eric learned to love them, too. He observed Johnny's relationships with his animals and Johnny's thoughts about people, and finally Eric came to formulate the Dgn' Theory: (Johny's last name)

Most people are feral.

If humans domesticated animals a hundred thousand years ago, animals domesticated humans, too. After all, they had to protect themselves against the danger of not being fed, and so they developed in their human "masters" a deep bond of affection for their animals. And that bond is instinctive, bred right into the genes of every human being on the planet. Every human being instinctively responds to animals with love.

The problem is that most people, escaping into the wilds of the city, have lost touch with their instincts. They are no longer capable of animal love. The truly feral person feels fear in the presence of animals. Like dogs and cats that have strayed back into the wild, many people are feral, too. His job, Johnny thought, was to bring people back to their natural instincts, and at least with Eric, he provided wonderful therapy.

Moats of Iris

Fire and water. Black and white. Johnny and Eric were a study in contrasts, as different from each other as could be.

Fire and water. Black and white. Johnny and Eric were a study in contrasts, as different from each other as could be.

Johnny was shy and generally reticent. Eric was outgoing and loved to talk. Johnny had a GED and a few years of business school. Eric had a PhD. Johnny made his living by the sweat of his brow. Eric pushed a pen and tapped away at keyboards. Johnny read the Metro section and the comics. He scanned the Board of Health notices to chuckle over which restaurants were closed that week for rat turd violations. Eric read the international section and studied the federal gossip. Johnny loved Roseanne, Eric NPR. For Johnny, food was function, to be eaten as quickly as possible in silence. For Eric, food was love, a celebration of human relations at every meal. Where Johnny saw the ugliest possible tie in the world, Eric saw beauty. Johnny loved color and high design; Eric continued to labor with the brick and board constructions that had dominated his sense of style since college. Johnny loved tools and knives and gadgets and rocks and stones in his pockets. Eric loved books and frying pans and everything in order. Johnny did the repairs; Eric did the paperwork. Johnny stood in awe and terror of authority; Eric would run his mouth, to his own eternal peril, if stopped by a policeman on the road. For Johnny, a doctor's prescriptions and dictums were law, for Eric they were the beginnings of a negotiation.

People marveled that they got along, much less built a life together. But they did build a life together and by the end had built a single identity they shared. For one thing, there was that energy from the very moment they'd met. It might have softened with time, but it was always there. They didn't need anything else and didn't want encumbrances. If the bond of emotion that held them together died, so be it, they thought. They'd separate. And given that both were very determined men, they fought to keep it alive throughout all the very hard spots.

It wasn't just the physical attraction that had later mellowed into love. They knew above all else that they could count on each other. If they gave their word, each could trust the other. They shared a skepticism about life in general and turned to each other's care as the years went by. They were devoted and loyal to each other beyond all else. Slights to one were insults to the other. They protected each other fiercely from the stings of the world and as best they could from the inevitable decay of life.

More than from the slings and arrows of the world, they worked to protect each other from the hurt and silence within. Each saw in each other a mirror of his own isolation. Both seemed destined to live with a core of vulnerability, and each saw himself as the other's protector. They'd finally bought the farm for their refuge, far away from the town and all its entanglements. They'd even begun to lay in their moats of iris.

As time went by, their shared identity was no longer merely psychological. They began to resemble each other physically. When they moved to the farm, new neighbors asked if they were related. No, no, Eric would say, just partners. Johnny, always vigilant, would kick him in the shins and say yes, cousins. No sense in making trouble, he'd say later in private.

At the hospital, after Johnny had been treated as best as could be and there was no more hope, the nurses became quieter, more gentle, as they waited for the day of discharge. Johnny was to be sent home under hospice care.

One nurse seemed to take special interest. As they waited for the day of discharge, Eric and Tona, Johnny's sister, were taking turns sitting with Johnny through the night. One night, when Eric was there, the nurse came in to see if either Johnny or Eric needed anything. She looked long and hard at the two - Johnny lying sunken and wasted, Eric sitting exhausted in a chair. And then, in a very soft voice, perhaps as much to comfort herself as to comfort them, she said, "You favor," she said. "You favor so. Are you brothers?"

Signs

These were the signs leading to the time of Johnny's death. Johnny was trying to prepare Eric for the storm that was about to bear down on them both.

These were the signs leading to the time of Johnny's death. Johnny was trying to prepare Eric for the storm that was about to bear down on them both.

For one thing, there was the newspaper. For years, Johnny and Eric had divided it up at breakfast, with Johnny taking the Metro section, and Eric taking the rest. After they moved to the farm, the paper was delivered every morning to the container at the mailbox. Eric would go out to get it while Johnny fed the animals, and they'd divide it up and eat. As time went by, and Eric began to get up a little later each day so he could sleep more, he'd pick the paper up on his way out of the driveway and leave the Metro section in the container for Johnny to retrieve later.

At some point, Eric noticed that Johnny had begun to leave it there. He asked Johnny why. It was too much to walk out, he said. So Eric made sure to bring it in before going on to work. But then, by the beginning of January, Johnny turned to Eric and said it wasn't worth leaving it any more. Actually, he hadn't read it in a long time. Not to bother anymore, he said.

There were the ducks, of course. When Johnny and Eric had moved to the farm, they'd found a wonderful shed already there, built for breeding dogs. Johnny fixed it up for the ducks with feeders and water pools and incubators all set out in a row. And then he brought the ducks over from the stables. They made a great fuss and took right to the place. After all, their mama was right there.

In September, Chani the filly had given Johnny a kick. It wouldn't heal properly, and then a hematoma set in. Finally, Johnny developed cellulitis. He was rushed off to the emergency room.

Johnny fought back hard and was released after a week. Over the years, he'd been in tighter spots than this. They both thought Johnny would snap right back, but instead, he slowed down. One day in October, he turned to Eric and said simply that it was time to get rid of the ducks. Just like that. Tona and her husband Don were visiting at the time. Johnny made arrangements for a neighbor with a pond to take them. On the appointed day, a Sunday, Eric and Tona and Don watched as Johnny gathered the ducks up. He was already partially immobilized, hobbling around on a leg that wouldn't heal.

There was the issue of what Johnny would eat. He'd always been a meat and potatoes man. That fall, Eric noticed he'd begun to eat less. At first he thought that Johnny had been snacking too much on the candy du jour in the afternoons. Then he realized that Johnny had begun to avoid red meat and favor chicken and fish, foods that he'd never particularly liked, and then from these to vegetables, foods in fact that had been next to anathema for all their time together. The last time they went out to eat, at Gambellini's Saturday-night-$10-a-head-all-you-can-eat- country buffet in Charlotte Hall, Johnny took a heaping plateful from the steam table, but only vegetables. Eric had been used to Johnny's quirks over the years, his sudden shifts in interests, and so discounted this as just another passing fancy. He was secretly pleased, believing that he'd finally prevailed on Johnny's taste.

There was the hay. Johnny and Eric had been buying the horses' hay a month at a time. Johnny didn't want Eric pitching too many bales around at one time, he said. Eric had a herniated disc, and so Johnny kept the number in storage low. But then, one day in November, he came back to say that he'd found a neighbor with almost 200 bales to sell and had purchased it. Eric didn't understand the sudden change in direction. He balked at the idea of having to store away so many heavy bales. Luckily, another neighbor offered to do the work for a bit of cash. It worked out fine, and they had hay to last well into the spring. But Eric didn't understand why so much.

For his part, Eric witnessed his own sign as he was preparing for the incoming hay. The previous owner of the farm had let years of scattered hay decompose on the barn floor. Almost immediately under the surface it had begun to mold and was dangerous for the horses. Both Johnny and Eric worried that the new hay would become contaminated, and so on the weekend before the hay was to be delivered, Eric went out to the barn to clean up the floor. Johnny was too tired to help and stayed inside that day.

Eric set about pitching old hay into a back stall, to be cleaned out later, maybe in the spring. At any rate, in the back it wouldn't do any harm. As he worked, the pitchfork hit something under the covering of hay. He bent over to scrape the hay aside and look. He found an old pile of mail: postcards from the 1980s, circulars, ads. Someone must have forgotten them there, where eventually they were covered by hay. Then he found a box.

It was a small cardboard box, wrapped in plain brown paper and tied with string. It had been sent in the mail to the farm address, but Eric didn't recognize the addressee. The postmark was at least fifteen years old. The return address was a funeral home. He opened it. Inside was an urn filled with cremains. An insert gave the name of the deceased - a woman unknown to him.

Eric considered what to do. Ordinarily, he would have taken it to Johnny, but this time, for whatever reason, he was unwilling to do so. Finally, he decided that the cremains were meant to be here with the property, and in respect to the deceased, he took the urn and scattered the ashes in the shadows of the trees behind the barn, well out of sight of the house. He could only hope that was the deceased's wishes. It unnerved him, but he wasn't sure why.

For years Eric called Johnny every day at 2:30 PM from wherever he was. Time to take your pills, he'd say, and Johnny would tell him what he was doing at the time. They both treasured those few moments stolen in private from the business of the day. They had converted the burdensome requirements of HIV pill schedules into a little ritual of love.

It was several months after they'd moved into the farmhouse. Eric called as usual at 2:30. This time, Johnny told him that the buzzards were circling for him. The farm was in a rural area, and there were buzzards. They would slowly circle around whenever they found carrion on the road or in a field. But this time, he said, they were circling around the house. Nothing new, Eric thought, must be something dead nearby, and he promptly forgot it. Later, once again, Johnny said the same thing, and Eric played it was a joke. A third time, after Eric got home in the evening, Johnny told him that the buzzards had come down and rested in the tree right outside the back window. He was afraid.

But the most potent sign of all was Papaw. Papaw was his grandfather on his father's side, a man with Native American background from an unregistered tribe. He'd come from the east Tennessee mountains and was buried with Johnny's grandmother Leona in Gatlinburg.

Papaw loomed large in Johnny's life. He was a figure of authority and spirituality. It came as a great puzzle to Eric, then, that three times, Johnny told him he'd had a waking vision of Papaw while he was working at the tack room at the old stables. Papaw, he said, had sent a bird to fly over him and circle back over his shoulder to Papaw. Then Papaw offered Johnny a bag with a pattern of black, white and yellow beads. It was very specific. And for Johnny, so real. He had, Tona later said, already begun his journey, way back then, back before anyone but Johnny himself had realized.

Johnny tried very hard to find out what the bead pattern meant. He was convinced it would tell him something. He went to several powwows to seek out the meaning, but ultimately to no avail.

So many signs! Poor Johnny, who struggled to fashion his own means to let Eric know about his journey to the end. Poor Eric, who struggled to decipher his mute testimony to that journey.

Sandals

After Johnny died, Eric cleaned out Johnny's old wooden chest and collected a few things in it that had been precious to them. It was his memory box. Among the things he put in the box were Johnny's sandals.

After Johnny died, Eric cleaned out Johnny's old wooden chest and collected a few things in it that had been precious to them. It was his memory box. Among the things he put in the box were Johnny's sandals.

Johnny was the sort of man who, if he could have, would have worn his boots twenty-four hours a day, certainly to bed, and probably even in the shower. But he couldn't. His feet were never very good. He had corns and planters warts and was constantly going to the podiatrist to have one or another shaved down or cut off. It got to the point where his boots and then even lace-up shoes hurt to wear them. This was the main reason why Johnny and Eric stopped dancing. It also prevented him from being able to judge rodeo properly, since a judge has to be able to run around the arena quickly. He just couldn't.

It wasn't just the corns and warts. His legs had begun to waste, and by the last year, he began to have trouble getting around at all. Johnny was a man of determination, and he hated having to rely on anyone for anything. His solution was to dig out a pair of beat-up black sandals that must have come from before they'd ever met. How he'd hauled those old things around without losing them, Eric never knew.

He began to wear his sandals instead of his boots. These he could just slip on, and for some wonderful reason, they didn't hurt the corns. By the time they'd moved into the farm, though, his ankles had begun to swell. No one seemed to know why. His boots were out permanently. It was all he could do to slip the sandal straps over his heels.

In September the filly kicked him in the right knee, and he developed a hematoma, and consequently cellulitis throughout his leg and groin. He parked himself in the emergency room and subsequently was hospitalized for a week with IV antibiotics. Once he got out of the hospital, he was reduced to crutches. Later, he graduated to the use of a cane. He used that cane until his last day.

Johnny's condition never stopped him. Every morning, he would pick his cane up from where it rested by the bed and draw his sandals to him, one at a time. Then he would carefully draw them onto his feet with the cane tip. If Eric tried to help, he'd shoo him away. Slowly he would make his way down the stairs and on with the day's business. He'd then proceed out to the barn and feed sheds, seeing that the horses and the dogs and -- until he finally had to give them away -- the ducks were fed and watered and properly cared for.

Eric remembered vividly the events of Tuesday, January 26. The inexplicable pain inside his chest that had developed the night before had not gone away. At the doctor's direction, they'd tried Valium as a palliative, thinking this was another case of the muscle spasms that had bothered Johnny for several years. The Valium, however, had only caused him to become incoherent and incontinent throughout the night. In the morning, the doctor said to come in right away. Johnny struggled to get his sandals on. He still wouldn't let Eric help. He was determined to maintain mastery where he could.

The doctor diagnosed him at the office with pneumonia and had him hospitalized immediately. Eric took him to the hospital just as he was- sandals, sweat pants and all. It'll be okay, Eric kept thinking. He's had pneumonia before. We can work it out.

As it turned out, the problems were massive, far beyond the complications of pneumonia and a collapsed lung. Johnny stayed in the hospital for a week and was brought home in an ambulance to hospice home care. They brought his sandals and personal effects home with him in a bag.

Throughout those three weeks at home, Johnny focused on mastery of his condition, and then, of his body, and then, finally, of his journey. He never once complained. He remained demanding of everyone who nursed him - Tona, Don and Eric. Despite the rapid wasting of his body and increasing loss of muscle control, he insisted on their helping to get him out of bed every day. The effort was such that for some time after his death, Eric continued to have back pains from the strain of lifting.

Slowly, painfully, he would walk as far as he could with the walker, at first by himself, then with help, then with Eric standing behind him in the walker just to hold him up as his legs would collapse out from under him. We're dancing, Eric would think. He would move the walker inch by inch forward with himself and Johnny inside it, as they moved their feet forward, step by step, pace by pace. By then, there was no more use of cane or sandals.

When he could no longer get out of bed, Johnny at least would move to the edge, more and more slowly every day until there was no movement left but a ghost, a shadow, a suggestion in the tremor of the hand of the motions needed to move on out of bed and back into the world. Then even that little motion ended forever.

There was a tremendous silence, a waiting, a holding of breath in the dimly lit room where Johnny had lain when Eric saw it again. He thought, Johnny's begun to walk in another world. Eric looked around the sick bed and saw the sandals tucked away under it. His heart sank. He thought how painful it must be for Johnny to walk barefooted, wherever he was walking. But then he realized that Johnny would be wearing his boots again, his beloved boots.

Eric put the sandals away with the boots and a few other items in the memory box. The sandals spoke of Johnny's fierce independence. He was, foremost, a true Tennessee man of grit and determination, of economy of means, of disdain of wasted motions, of a will always to move forward, wherever the road took him.

Eric loved Johnny's sandals.

Eyes

Johnny had the most beautiful eyes. They were blue and clear, and for all the years they were together, Eric loved looking into them as deeply as he could.

Johnny had the most beautiful eyes. They were blue and clear, and for all the years they were together, Eric loved looking into them as deeply as he could.

During the weeks Johnny lay sick and dying at home, his eyes grew tired and then cloudy. Within a week they were closed most of the time, and when he opened them, it was hard to tell if he could really see what he was looking at. Then they remained closed most of the time, and then all of the time. They were bruised, crushed and sunken. The light had gone out.

As Johnny lay dying, his eyes looked exactly like the eyes of the baby chicks he had loved to raise. He would gather fertilized eggs from the most amazing places and put them carefully in his incubators. He monitored the temperature and humidity to keep them viable. As the time came closer, he would go out to the hatching shed at night and candle the eggs in the dark to see which were viable and which were not. Those that weren't, he regretted but disposed of. He knew there would be those that would hatch.

There would be the first pinpricks on the shells as they began to peck. Sometimes, if Johnny were lucky, he would even be there to hear the sound of the tiny beak pipping against the shell. In his excitement, he would help hatch the chicks out of their shells. He was careful not to break the shells, which would have killed the chicks. Instead, he only helped remove broken shell as the chicks pecked through. When they emerged, small, shriveled and quivering, he would cradle them in the palm of his hand and warm them and coo to them until they stopped shaking. Then he would put them under the heating lamp to let them start drying out and wait with great anticipation to see which egg might be next.

Bruised, crushed and sunken at first, the chicks' eyes would grow stronger each day as they dried out, stood up, began to eat, drink and move. Their dark eyes, now fully opened, would grow clear and luminous. They had come fully into this world.

As Eric looked at Johnny's eyes in those last days, he was struck how much like those chicks Johnny himself now looked. Eric thought, maybe it meant that Johnny was returning back from this world to emerge somewhere else, that God would cradle him in his hand to warm him and love him, that God would protect him, just as Johnny had loved and cared for his chicks.

Eric loved Johnny's eyes.

February 19

Johnny died at 5:40 PM on Friday, February 19, 1999. At that moment, Eric was checking out of a hotel in Okinawa, Japan, waiting for transportation to the airport to begin the 24-hour trip back home. He first learned of Johnny's death when he arrived home late on the afternoon of Saturday, February 20.

Johnny died at 5:40 PM on Friday, February 19, 1999. At that moment, Eric was checking out of a hotel in Okinawa, Japan, waiting for transportation to the airport to begin the 24-hour trip back home. He first learned of Johnny's death when he arrived home late on the afternoon of Saturday, February 20.

For two years Eric had been central to planning a major conference with Japanese counterparts. This was his work. The appointed dates for the conference were February 17 to 19; the place was to be Okinawa, Japan. The occasion was important, and providing the extensive technical background that the US team needed was Eric's work.

Both Eric and Johnny had been proud of his work. They had known for a long time that these were his plans. As the time came nearer, it also became apparent that it would strike in the midst of Johnny's final crisis. There was no answer to the dilemma. By this time, Johnny had already lost the power to talk. His vital signs remained strong, but he no longer could eat. He had not had more than a few eyedroppers of water in several days. He didn't have the strength or will to swallow. His body was wasting.

Eric decided to go but cut back the schedule to absolute minimum: just enough time to move into the heart of the conference and return immediately after its conclusion.

The time to depart came. It was early Sunday morning, February 14. Eric had to leave by 6:30 AM if he were going to catch the plane from National to Tokyo. He came to Johnny's bedside in the makeshift sick room they had made of the downstairs just after 6:00 AM.

It was dark outside and inside. Only the night light was on - a soft Japanese paper lantern in the shape of a pyramid in a corner of the room. Eric sat down in the stool by the side of the bed. They'd put it there to make feeding Johnny and holding his hand easier. The temporary table with all the medications, wipes and clutter of sickbed paraphernalia was behind him.

He took Johnny's hand. It was hard to tell if Johnny was awake or not. His responses were no longer certain. He remained silent, eyes closed. Eric told him it was time for him to go, that he'd be back in six nights, and that Johnny was to wait for him, no matter what. He continued to talk to him briefly in this manner, and when he thought he'd said as much as he could, he moved to go.

At that moment, Johnny responded. He said nothing, he didn't move, he didn't open his eyes. His hand simply grasped Eric's hand tightly, more tightly than Eric had thought possible for him anymore. Eric sat back down and held on to Johnny. They remained like that for some time in silence. Johnny then relaxed his grip. Eric leaned over to whisper goodbye. He kissed him and told him once again that he smelled good with his lotion. Eric went out to the car and drove off to the airport in the dark.

Eric called back home from Japan as soon as he settled into his hotel room and twice a day after that, morning and night. The conference ended Friday night, and he checked out of his hotel room at about 7:30 AM the next morning, after having made a final call home. For the first time, Tona, who was nursing Johnny for the week with Don while Eric was gone, said his vital signs had begun to deteriorate. She was using the cordless phone.

Eric asked Tona to put the phone up to Johnny's ear. She did. Into the silence Eric told Johnny that he was on his way home, to wait for him if he could, but that if, just if, Johnny couldn't wait, if he had to go on ahead, it was okay, he'd understand. He said this several times. Silence continued from the other end. He hung up the phone in Okinawa and began the long journey home.

There was little to be said for the journey home except for the tension. When he arrived home, it was already dark. He walked in. Tona and Don greeted him, and then Tona gently told him what had happened.

He went into the living room. It was empty. The rental company had already picked up the hospital equipment and oxygen tanks. Only the soft glow of the night light in the darkness remained the same.

Eric wept. Tona and Don did what they could to provide comfort in the midst of their own grief. When it was quiet again, Tona told him the following.

While Eric had been talking to Johnny through the phone from Japan the night before, she noticed rapid eye movement beneath the thin, closed lids. Johnny died very shortly after that. It was a sign, she said.

The Magic of Night

Johnny was a Navy man. He'd signed up in 1962 and served aboard the USS Cone in the Mediterranean, a proud if young and very pretty sailor boy. He'd learned to tie all sorts of wonderful knots while on the ship and used them for the rest of his life in every imaginable situation. He'd also learned to identify several constellations from the ship's deck at night.

Johnny was a Navy man. He'd signed up in 1962 and served aboard the USS Cone in the Mediterranean, a proud if young and very pretty sailor boy. He'd learned to tie all sorts of wonderful knots while on the ship and used them for the rest of his life in every imaginable situation. He'd also learned to identify several constellations from the ship's deck at night.

Shortly after they'd moved to the farm, Johnny called Eric outside one night. It was mid-August, and the night sky was dark that far out from Washington. It was an absolutely clear night. A flood of stars sparkled above, virtually covering the tops of the trees.

Johnny pointed out the constellations he knew. Eric knew only one, the Big Dipper. Both could see it pointing in its vast reach to the north, past Annapolis, past Baltimore. They sat down together in the swing and stopped their work of unpacking boxes, so that they could enjoy the night.

On Sunday, two days after Johnny's death, Eric walked out of the house in the morning for some chore or other. Its purpose escaped him, but he found himself staring at the dull winter sky. It had no interest for him. It appeared ugly, like a scab formed over the open wound of night, he thought. He was impatient for the comfort of the living room in the quiet of the night, lit only by the small night light, where he'd last talked to Johnny alive.

That day, or maybe the night before, Tona told him some more bad news. Johnny's youngest brother, Buddy, had suffered a massive heart attack on Friday night when he'd heard the news of Johnny's death. He was down at a hospital in Knoxville, where they'd taken him from Morristown. He was not expected to live. She was the only member of the family available to nurse him. They'd have to leave for home very soon. Eric, Tona and Don talked. They agreed to wait until Tuesday, and then Tona and Don would leave.

Tuesday came, the parting was painful, and then Eric was alone. Throughout January, even before Johnny had been hospitalized, he'd imagined himself alone like this. He'd imagined himself alone with the stars at night, when he could find Johnny up against the night sky as a new, secret constellation that only Eric could know. He had not imagined the depth of the loneliness he would feel.

Eric continued his chores during the day. There was much to do to straighten up the house. There was all the paraphernalia of the sick room to put away. Beyond that, there was the process of moving in that had been put on hold months before, as Johnny grew weaker. There were numerous accounts to close, papers to sign, numbers to call, all the bureaucratic chores of death.

Late that night, Eric went to walk Shiki outside before turning in. It was the only time of day when Eric could find some relief.

Outside, it was cold under a cloudy sky; the stars were nowhere to be seen. As he walked Shiki about the yard, it began to snow: big, dry flakes slowly floating down. He put his arms out and up, as if to draw the flakes into himself. The flakes felt warm, as if they were enveloping him.

It's Johnny's love, Eric thought. He's there, spread out among the stars, pouring his love down in me. He died for me, he thought. He didn't just die, he made a sign of his death, he used his death to tell me he'd understood what I'd said, that it's okay to let go, he'd understand. That was how much he loved me, he died for me. He literally died for me.

It continued to snow. Shiki finished her business and came back to Eric. They went inside. Eric sat down next to the soft light of the paper lantern and stared at it, searching again for the feeling of warmth that seemed to be growing colder and more distant.

The Dance

Johnny and Eric had loved to dance. Just about every weekend of their six years in Knoxville, they'd make their way to one or another of the local gay bars and dance until closing time. They knew every good dance bar between Louisville and Atlanta. When they got to Washington in spring, 1983,they made their way first to one, then another of the dance bars and finally ended up going to the Equus, a neighborhood bar in Capitol Hill.

Johnny and Eric had loved to dance. Just about every weekend of their six years in Knoxville, they'd make their way to one or another of the local gay bars and dance until closing time. They knew every good dance bar between Louisville and Atlanta. When they got to Washington in spring, 1983,they made their way first to one, then another of the dance bars and finally ended up going to the Equus, a neighborhood bar in Capitol Hill.

There was a fresh wind blowing in the gay scene then. They started frequenting the Equus just at the time it underwent a change in format, from disco to country & western. The management provided an instructor, Ron the Texan, who got everyone out on the floor to learn. Awkward as they might be, everyone did it. The men didn't just do it: they loved it. They were dancing with someone again, after all the years of solo disco flights.

Johnny and Eric tried it and loved it along with everyone else. There was the schottische, the ten-step, the barn dance and every week a new line dance to learn. But their favorite remained the first dance they learned -- the two-step. Slow, fast or dirty, it was their dance.

At first Eric led, and that pattern held for a long time. But slowly, for whatever reason, it began to change, and they found themselves dancing with Johnny in the lead -- hat off and held behind Eric so they could put their heads together, holding each other tight. They danced every weekend until closing time.

In time Eric was sent off to Japan for four years on his job. He'd come back for a few weeks twice a year, and Johnny and Eric would dance, but things changed. Styles changed, dances changed, people changed, bars changed.

Johnny went out to Japan to join Eric for the last half year. When they finally came back to Washington for good, they found they were out of the scene. They wanted to dance, but somehow the will wasn't there. Johnny's feet got worse, and he began to waste - nothing spectacular at first, but his energy was down.

Their dancing years were over. Johnny continued to listen to C&W. Garth's "The Dance" was his favorite. Eric lost interest even in that much. It all seemed a ghost of the past.

After Johnny came home from the hospital to hospice care, Eric put a radio by the bed for Johnny to listen to. He spun around the unknown channels. By chance, he stumbled across 102.9 FM, WKIK, "California Country." (What was 'California' country, anyway, Eric wondered.) The C&W it played was soft, old and slow. It was filled with loss and yearning and searching. The nostalgia of it comforted Johnny and Eric. They remembered, if only very briefly and dimly, how it used to be. Eric left the radio on for Johnny to listen to, and he took comfort in it.

After Johnny died, Eric wrapped himself up in the farmhouse in his grief and loneliness. He kept it dim to preserve the moment of saying goodbye as he remembered it. He burned vanilla-scented candles for the scent of the cocoa butter he had used to rub Johnny down, trying to keep his skin intact - futilely, as it turned out. He said prayers for him every night and talked to him.

Wherever he was, whenever he could, he would turn on the radio to 102.9 and crank it up all the way. He studied every word of every song, trying to find meaning in them that he had never recognized before. Each statement of loss, every adjustment to it, each search for a path out - he clung to them.

Time went on, and the grief and loneliness only became worse. Eric went to a therapist. It was a last resort, and he was reluctant. Pay for such things! he thought, when people should be able to reach out to each other freely and tell them their problems as friends. What is this, he thought - an escort service of the heart?

The therapist's name was Gordon. Gordon was a compassionate, gentle man. Eric was taken with him, to his surprise. Gordon simply listened to his grief and let him cry or laugh as he felt.

Every night Eric would drive home from work and turn the radio on to 102.9. It wasn't any good in the District. All he'd get was static, but he left the radio on full blast anyway. It was like an early warning system. By the time he'd get to Clinton, WKIK would begin to come in, and at the Brandywine turn, it would come in strong and fierce. He was in heaven.

One night he stopped to wait for the red light at the Brandywine turn, and an old two-step was playing. That's when it happened. Suddenly, Gordon was with him. He certainly hadn't been there before. Eric hadn't been thinking about him, but there he was, smiling and dressed in western to the hilt, topped in a black Stetson. Then, just as suddenly, Eric was dancing with him! He wasn't just dancing: he was leading and looking deep into Gordon's eyes. It was shocking and sensual all at once. Someone honked behind him. The light had turned green. It was all he could do to remember to drive on.

The image recurred more and more frequently as the days went by and Eric would listen to the radio. It no longer contained itself to dancing. He had an irresistible desire to flirt outrageously with Gordon, to pose, to touch. In the end, it always came back to the dance. With Gordon it was like a dream: perfect timing, coordination, body language. Gordon responded to every signal and suggestion. It was being back together with Johnny, and for that while, he felt very good.

He told Gordon about this. Gordon encouraged him to deepen the bond with subtle clues and suggestions of his own interest in the C&W scene. For all Eric knew, it might be an extravagant, luxurious lie, simply a means to provoke Eric's fantasy. Whatever Gordon's motives, the feelings were real, and Eric trusted him. Gordon's interest seemed to lie in letting him look at what lay within and what it meant, not at Gordon himself.

And draw them out Gordon did, at length and at depth, but not without a price. There still was Johnny. There still very much was Johnny. Johnny was still alive. Eric didn't know what to do. At night, when he'd light the candle and say prayers, he would talk to Johnny. He let Johnny know what was happening, carefully and indirectly at first and then more openly.

He was coming home after work at the Brandywine crossing again, with 102.9 cranked up. An oldie was playing, and Eric and Gordon were dancing, when Eric had it. He turned and called Johnny and told him to take a look at all that was going on. What are we going to do about it, Johnny? What can I do? I just can't help this. He felt despair.

Johnny was there. He looked at Eric and Gordon. He didn't say anything. He never would have, anyway. He smiled at Eric, took off his hat and cut in on the dance. Off he danced with Gordon, Johnny in the lead. He took him away, to enjoy him by himself for a little while. Who knows, maybe they went off to rope some calves, or, God forbid, even compare notes, Eric thought. This time, he drove on, suffused in their warmth.

May your spirit be with us, Johnny.

May your soul be in heaven.

May your heart be with your friends who went on before.

May your eyes be on us, forever.

Be in peace, Johnny.

May peace be upon us all.