WHEN A ONE-TON BUCKING BULL IS tossing you around a rodeo arena like a rag doll, who's the clown you want watching your back?

Ronald or Bozzo? Sideshow or Krusty?

Yeah, right. What you need is a rodeo clown, and fast.

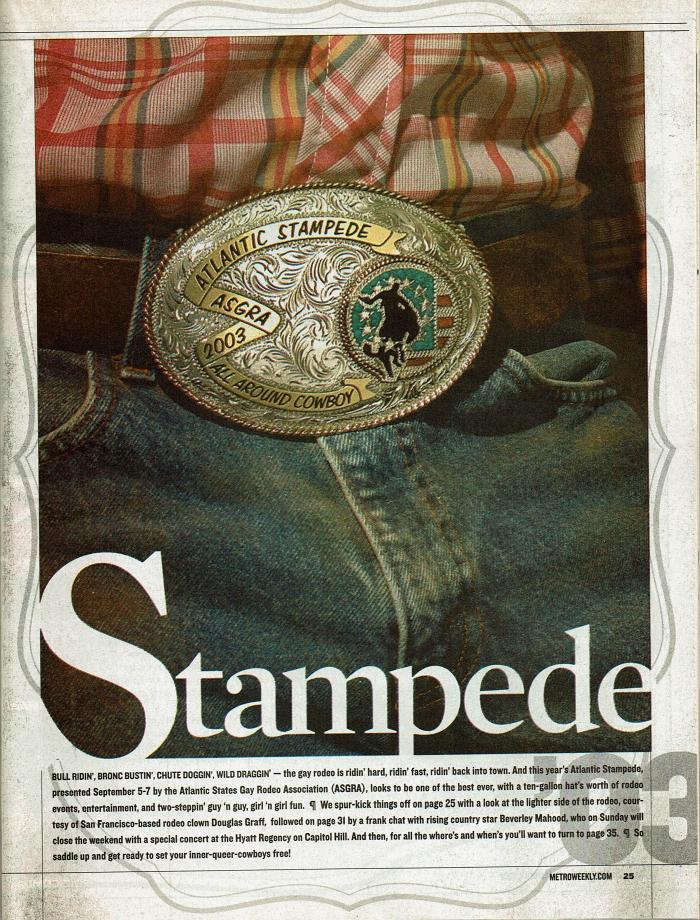

They may not have the big shiny pants or the preposterously large feet or even the red ball nose, but the rodeo clowns have a style all their own. They're the ones who pull thrown riders out of harm's way. They're the ones who make sure that 2,000 pounds of beef runs this way, not that. And they're the ones that keep the crowds laughing and cheering throughout the day.

That's the goal for Douglas Graff, one of the two clowns who will be gracing the arena at this weekend's Atlantic Stampede.

"I'm a clown at heart," he says. "There's nothing like a spotlight on me or a microphone in my hand."

A former Wisconsin farm boy who as an adult joined the dot-com migration to Silicon Valley, Graff is the former Mr. International Gay Rodeo 1999, and a regular fixture on the gay rodeo circuit where he got his start as a competitor before becoming a clown.

"After you get over 30, you don't heal as easily," says the 36-year-old. "I've broken a shoulder, torn a rotator cuff, and gotten a screw in my elbow. At some point you think, maybe I should back off a little bit with competing."

Since he first filled in for a clown in L.A., Graff has found his new niche in gay rodeos across the country, helping both with the entertaining and the safety of the competitors.

"I've been a competitor and I know how important the clown is to the riders," he says. "I've been a rodeo director and I know how important it is to put on a show for the audience."

METRO WEEKLY: Did you like being on a farm growing up?

Douglas Graff: It was a great place to grow up. When you're a kid there's no better place to be than in the country, and if you like animals a farm is a wonderful place to be. But then you get older and discover there's a bigger world out there, and you realize just how hard it is to make money being a farmer. That was probably the biggest thing that made me decide farming wasn't really for me - I realized that it was a lot easier to make money Monday through Friday than Sunday through Sunday in rainstorms and hailstorms and all that weather crap. I decided that it was right for me to move to the city, so to speak.

MW: How did you first get involved with gay rodeo?

GRAFF: I was out here in California on a work assignment and I met this cute cowboy. He said there was rodeo coming up in L.A., and I should come down for it. So I went to what turned out to be the tenth annual L.A. rodeo, which was the largest gay rodeo in the International Gay Rodeo Association's history. I was still pretty much a Midwestern farm kid, and I saw country folk being gay in this large setting with all this excitement, and raising money for AIDS charities. I had to be a part of it. I went back [home] to Michigan and I happened to discover that it was the very year that the Michigan Gay Rodeo Association was just getting started. I was involved with those first two rodeos there before I moved to California.

MW: Back on the farm, did you ever participate in a rodeo?

GRAFF: No, but I did have a horse that I took to the county fair when I was in high school. That was about it.

MW: How old were you when you first got thrown from a horse?

GRAFF: Hell, probably four years old. My sister and I would go out and just jump on them and ride. We were farm kids, we had no fear - you bounce when you're that age. AS an adult I respect horses a great deal. I do some pleasure riding, but I don't compete on horses. I've broken so many bones now that I've developed more caution around horses. Going full-out running now is not something that I really look forward to doing on horses.

MW: You said earlier that after all your broken bones and injuries, you were looking for ways to stay involved without putting your body at the same level of risk. When was the first time you thought "I want to be a clown?"

GRAFF: When I was Mr. IGRA, [a California chapter] called me a couple of weeks before their rodeo because their clown had backed out on them unexpectedly. They said they knew I hadn't done this before, but they thought I'd be good at it. And it was a blast. That's when I decided that. Since I was getting older and it made sense for me to move on to doing something else, being a rodeo clown was something IGRA needed.

MW: What exactly does a rodeo clown do?

GRAFF: If you go to a rodeo you're going to see two types of clowns. For the bullfighter [clown], his number one responsibility is the safety of the rider. He's there is case a rider comes out of the chute and gets in trouble - the bullfighter gets the rider out as quickly as he can, and also distracts the animal away from the rider. Whereas my duties [as the second type] are for the show. If somebody goes down and gets hurt, it's my job to get the audience's attention back to having fun. People come to have fun, to be out in the country and enjoy themselves. It's my job to make sure they do.

MW: Do you have a routine that you do while in the arena, or is what you do improvised?

GRAFF: It's very spontaneous. At some rodeos, if they're humming along fast they don't necessarily need filler. But I have a pocket full of jokes that I carry with me and I've got some long stories that I tell if I need to. We have one skit in our back pocket for the Atlantic Stampede if we have time. It really depends on ow much time we need.

MW: How do you pill together a clown outfit? Do you have any guiding principles as to what a rodeo clown should look like?

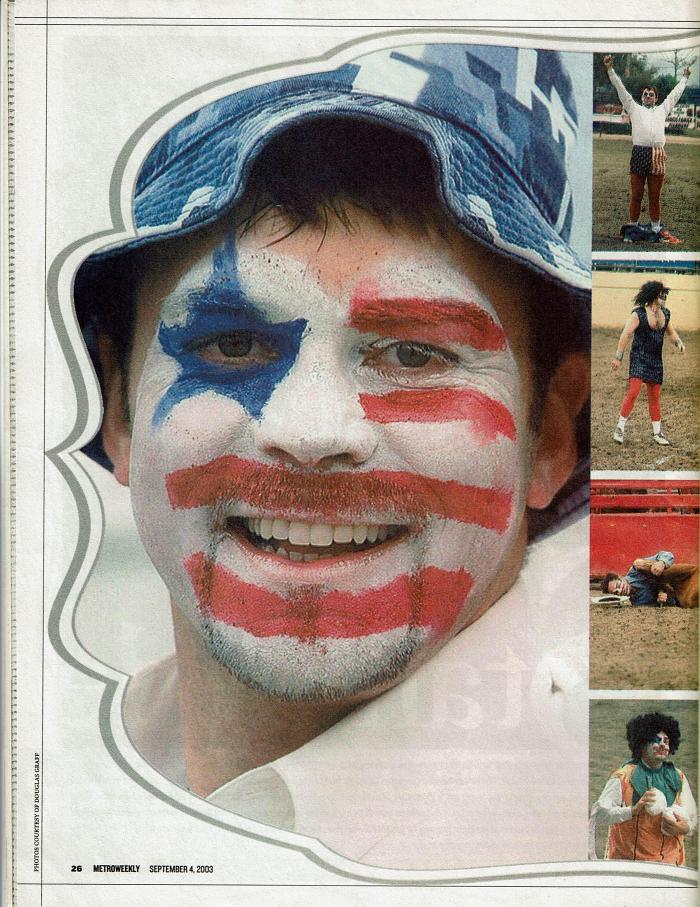

GRAFF: Number one is safety - it's got to be something I can move quickly in. A lot of it I've picked up over the years. Somebody gives you something, or you see something and you just pick it up. My make-up has changed a great deal [over time], and my hair because I use my own hair now. I used to wear goofy clown wigs, but now I pretty much just wear the old hat and concentrate a more on my make-up. There's a big difference between a circus clown and a rodeo clown. The circus clown has big, draping clothing with big shoes. That's just not safe for a rodeo clown - we've got to be able to jump up, get out of the way and help the bullfighter.

MW: Rodeo clowns seem to have more of a hobo look as opposed to a circus look.

GRAFF: I haven't studied a lot about clowns, but everybody has their own unique look. It's about going out and being fun. When [I clowned] at the San Diego rodeo in September 2001, ten days after September 11, that was about, "We're here, dammit, and we're not going to crawl away and hide." It was about not only going out and being gay, it was about being American and being proud. That was the hardest rodeo I've ever clowned at. They knew they had to be there, they wanted to be there, but they felt guilty for having fun with me. It was really tough to get the crowd motivated, but we did it. We did it through patriotism. I had on my red, white and blue flag shorts, and I did my face in red, white and blue with a star, all very patriotic. That really helped and gave them something to be engaged with.

The think I look out for most of all is to get the audience connected with what's going on in the arena. The announcer's job is to get out the facts. My job is to connect what's going on in the arena with the people in the crowd, so they know why something just happened, or to get them to know a contestant a little better. I know almost all the contestants on the circuit, being involved for so long, so I'll tell a little story about them to the audience. Sometimes that gets me in a little trouble with a contestant, but they all know that it's there for the show. If the audience is connected to the show, then they'll come back. And it's all about getting them to come back and enjoy what we do so we can continue to do it.

MW: How different is gay rodeo from mainstream or non-gay rodeo?

GRAFF: There are a couple of different categories of non-gay or mainstream rodeo. You have professional rodeo, which are the people making massive money doing rodeo, and then there are the many amateur rodeo circuits out there. IGRA is a pro-am circuit dominated by gay contestants - we have several straight contestants as well, and that's great. The major differences between gay and non-gay are that in gay rodeo our women do everything that men do. We have women bull riders, women bronc riders. Our men do everything that the women do, so we have men that run barrels. If you go to a pro rodeo, women would never ride bulls or broncs and men would never run barrels. We also have our starter events, what we call our camp events. Pro rodeo doesn't have any starter events, because they're professionals. It's like the difference between the San Francisco Giants and your neighborhood softball team, to some degree. It's hard to compare us to them. But the major difference is that women do events you wouldn't see them in the pro rodeo or many if the amateur rodeos.

MW: Are there any similarities between gay and n on-gay rodeos that stand out for you?

GRAFF: The animals. WE ride the same kinds of animals that non-gay riders ride. Bulls don't know the difference. They buck just as hard with a gay rider on them as they would with a straight rider, and whether it be a man or a woman.

MW: Are gay rodeos making gay and lesbians a bigger and more accepted part of the country and western scene?

GRAFF: Well, I can't help but think that familiarity is always a good thing. For example, we rent our stock from people who provide stock not only to gay rodeos but to other amateur and sometimes even pro rodeo. So when they come and see how we run our rodeos and get familiar with us they understand that we're just people too. Speaking from my own experience, this year we moved our rodeo to a coastal area of California that some might call a very redneck area. It was at a working ranch with a rodeo arena we rented. By the end of the weekend the ranch staff knew we were just folks out there having fun. I can't help but think that because we went into that area of the country and did what we did, many people were exposed to openly gay people for the first time. Now they have a different understanding of who we are and what we do - we're really just people.

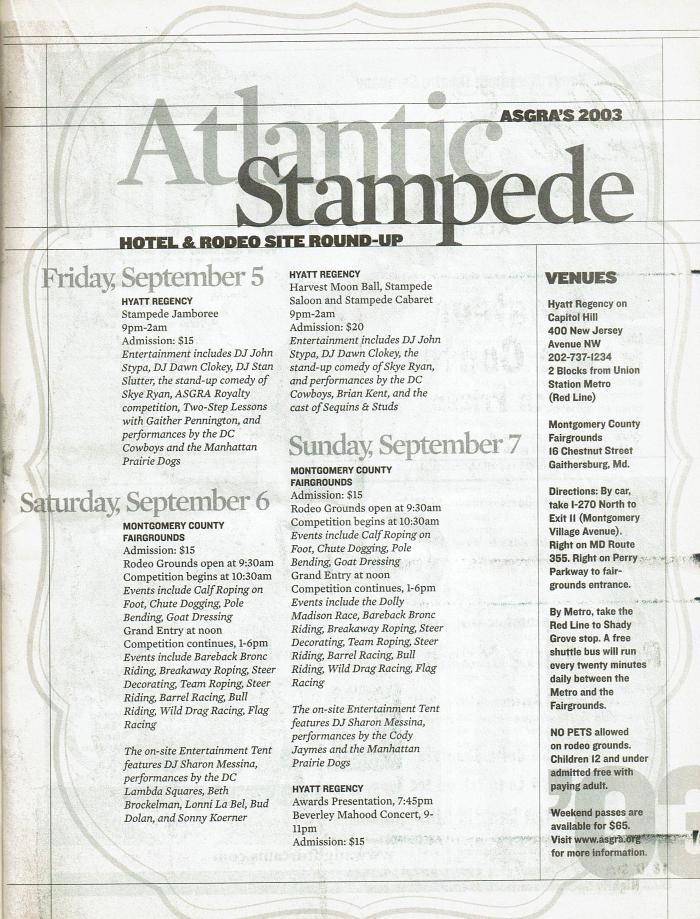

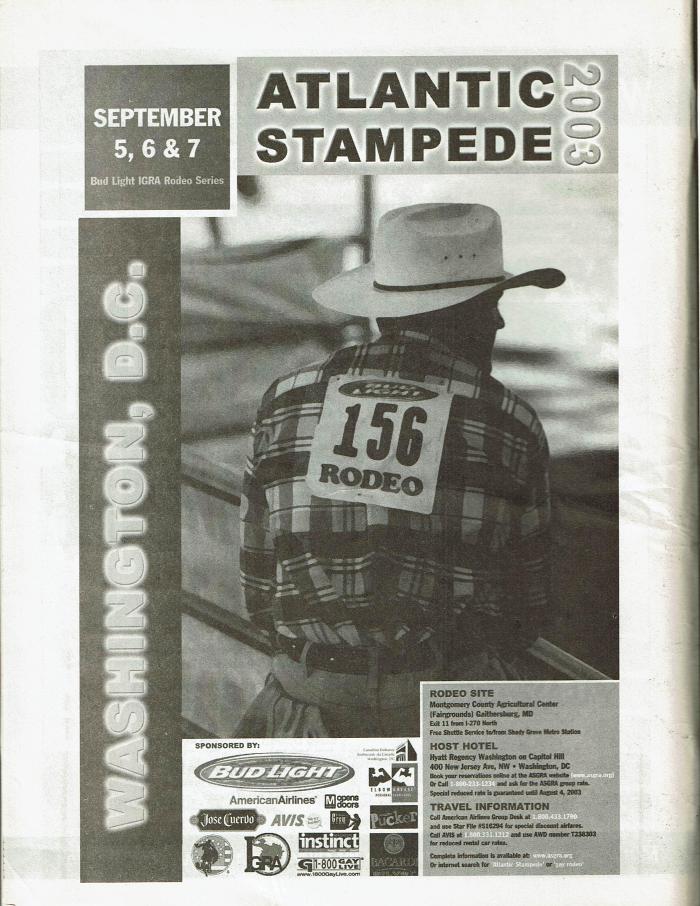

Douglas Graff will appear at ASGRA's Atlantic Stampede 2003 this Saturday and Sunday, Sept. 6 and 7. For a complete listing of events, see page 35.

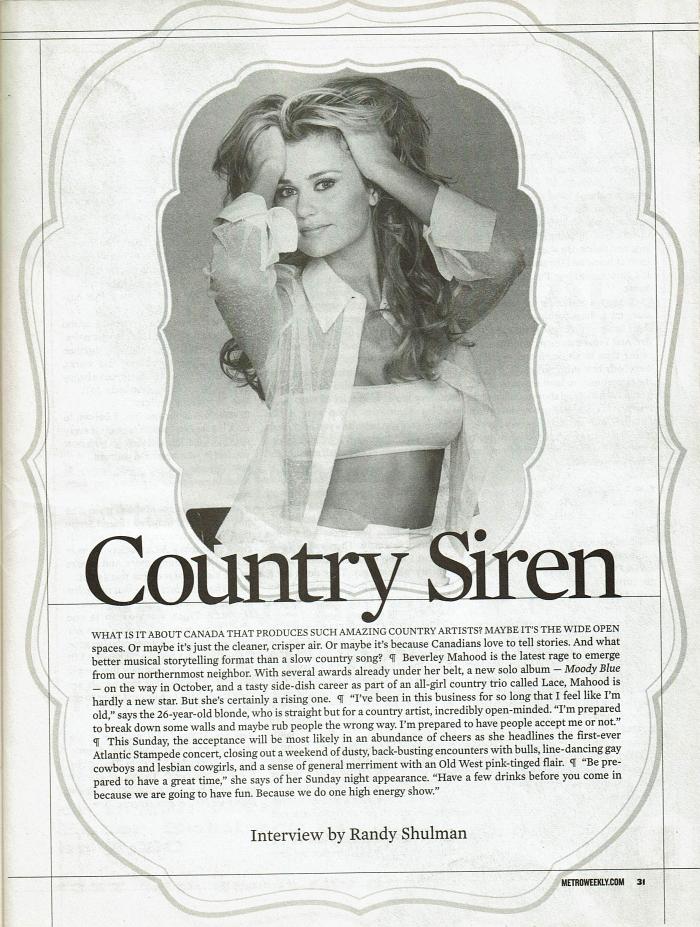

Country Siren - Interview By Randy Shulman

WHAT IS IT ABOUT CANADA THAT PRODUCES SUCH AMAZING COUNTRY ARTISTS? MAYBE IT'S THE WIDE OPEN spaces. Or maybe it's just the cleaner, crisper air. Or maybe it's because Canadians love to tell stories. And what better musical storytelling format than a slow country song?

Beverley Mahood is the latest rage to emerge from our northernmost neighbor. With several awards already under her belt, a new solo album - Moody Blue - on the way in October, and a tasty side-dish career as part of an all-girl country trio called Lace, Mahood is hardly a new star. But she's certainly a rising one.

"I've been in this business for so long that I feel like I'm old," says the 26-year-old blonde, who is straight but for a country artist, incredibly open-minded. "I'm prepared to break down some walls and maybe rub people the wrong way. I'm prepared to have people accept me or not."This Sunday, the acceptance will be most likely in an abundance of cheers as she headlines the first-ever Atlantic Stampede concert, closing out a weekend of dusty, back-busting encounters with bulls, line-dancing gay cowboys and lesbian cowgirls, and a sense of general merriment with an Old West pink-tinged flair.

"Be prepared to have a great time,' she says of her Sunday night appearance. "Have a few drinks before you come in because we are going to have fun. Because we do one high energy show."

METRO WEEKLY: What is it that made you decide to pursue a career in music?

BEVERLEY MAHOOD: Ever since I was a child I've always loved being on a stage - I remember from the age of three just wanting people to look at me, so I'd stand up on top of my parents' coffee table and sing and dance. On stage is where I feel most at home and the most comfortable. It's just something I've always loved doing.

Music is a chance for me to write and share my feelings within my song, things that I believe in, things I go through every day. And I find that easier to do in a song rather than to sit down and explain to somebody in a story. So I guess I've had the opportunity to have music in my life to express how I feel about myself and the things in life. It's like I was meant to do it. I get to live out my dreams every day.

MW: You started when you were pretty young - you met your current producer when you were twelve.

BEVERLEY: I did, so I've been in this business a long time. Kids used to go to camp when they were kids. I spent my summer months at a recording studio recording jingles.

MW: Had you been writing songs as well as a teenager?

BEVERLEY: My producer introduced me to my current manager when I was nineteen. And they said, "We're not going to do a record with you until you write at least one song." So that was the challenge. One of the first songs I wrote was called "Girl Out of the Ordinary." It was the neatest thing to express yourself in a song about what you've grown up through, feeling like "Maybe I'm no different."

MW: Did you feel different from everybody else back then?

BEVERLEY: People looked at me as kind of weird. I never fit in at school. I always was the different child. My parents always moved around, they could never really settle down, so I didn't have many friends. Until I wrote "Girl out of the Ordinary," I didn't realize how many other people were just like me. Everybody in life goes through things that sometimes they don't talk about until somebody else talks about it. And then they're able to say, "That's me."

MW: What types of things for example?

BEVERLEY: Never fitting in. Always being the new kid on the block. Going through high school and public school with kids just doing cruel things. Kids are not kind. Kids can be cruel. They used to put tacks in my shoes, throw my gym clothes into the toilet, put my hair - I used to have really long hair down to my bum - between the two backs of the desks so I'd get up and my hair would rip out. Now those same people come up to me and say, "We were kind of mean to you as a kid, but wow, look at you now!"

MW: What was it about country music in particular that attracted you?

BEVERLEY: When I started writing, that's where my music tended to fit because country music is in a lot of ways storytelling. Sometimes a pop song is like, "Yeah, love you baby, love you baby. Yeah, yeah." But country music is like opening up a book for three and half minutes and finding out a story.

MW: Your concert closes this weekend's ASGRA rodeo. There are some country artists who, I imagine, would be little hesitant to be attached to a gay rodeo.

BEVERLEY: Then you know what? You don't want that artist. There's a lot of people that I know of in the country music industry who are gay. They don't say it because it's not the proper thing to do, but they are gay and I can't wait for the day that they come out.

MW, I accept people at face value. As long as they're happy and they're not hurting anybody, who cares [whether or not they're gay]? [When I played the gay rodeo in Calgary], the interaction with the audience was unbelievable. We had a blast.

And I'm looking forward to [ASGRA], I know that they're audiences that will listen. My best friend is gay and he's the guy that I will play songs for and say, "Okay, I have twenty songs because I have over-recorded for my record. I'm gonna give you a week and then you're gonna come back and tell me which ones you like."

MW: It's kind of like queer ears for the straight girl. Do you remember the first time a gay friend came out to you and how you responded?

BEVERLEY: One of my best friends did come out to me and say, "I think I have gay tendencies." She was very, very nervous about it, but it didn't shock me at all and I supported her. I said, " You have to be happy in life, life is too short for you to not be able to be who you want to be as a person or who you want to be with."

MW: How old were you when that happened?

BEVERLEY: Seventeen. I guess I sound enlightened, but the thing is that nowadays [straight] couples can't stay together. So if you find something that works, make it work. And as long as you're happy and you're not hurting anybody, do it.

MW: No religious conflicts?

BEVERLEY: Not for me. Yes, I believe in God, but do I go out and promote it every day? No. I feel like you must go with how you feel in your heart and your gut.

MW: Canada recently made history in North America for legalizing gay marriage.

BEVERLEY: I thought that was great. The first thing I said to my gay friend Sergio was, "okay, so when are you getting married?" [Laughs.] As a society Canada tends to accept things more. And if we're on the leading edge of this, that's great.

MW: What's the best thing that music has brought to your life?

BEVERLEY: That's wrapped up in one word: acceptance. As a person with her own feelings and emotions, who has gone through life and felt like "Where do I fit in?" I find that it's important that people like you. It's important that people see your train that's moving and want to get on board.

Beverly Mahood will perform at the Hyatt Regency, 400 New Jersey Avenue, Sunday, September 7, at 9 p.m. The concert is open to the public. Tickets are $15. For more information on ASGRA's Atlantic Stampede 2003 events, see page 35.