PETA Protests Humane Rodeo

By Tricia Toney

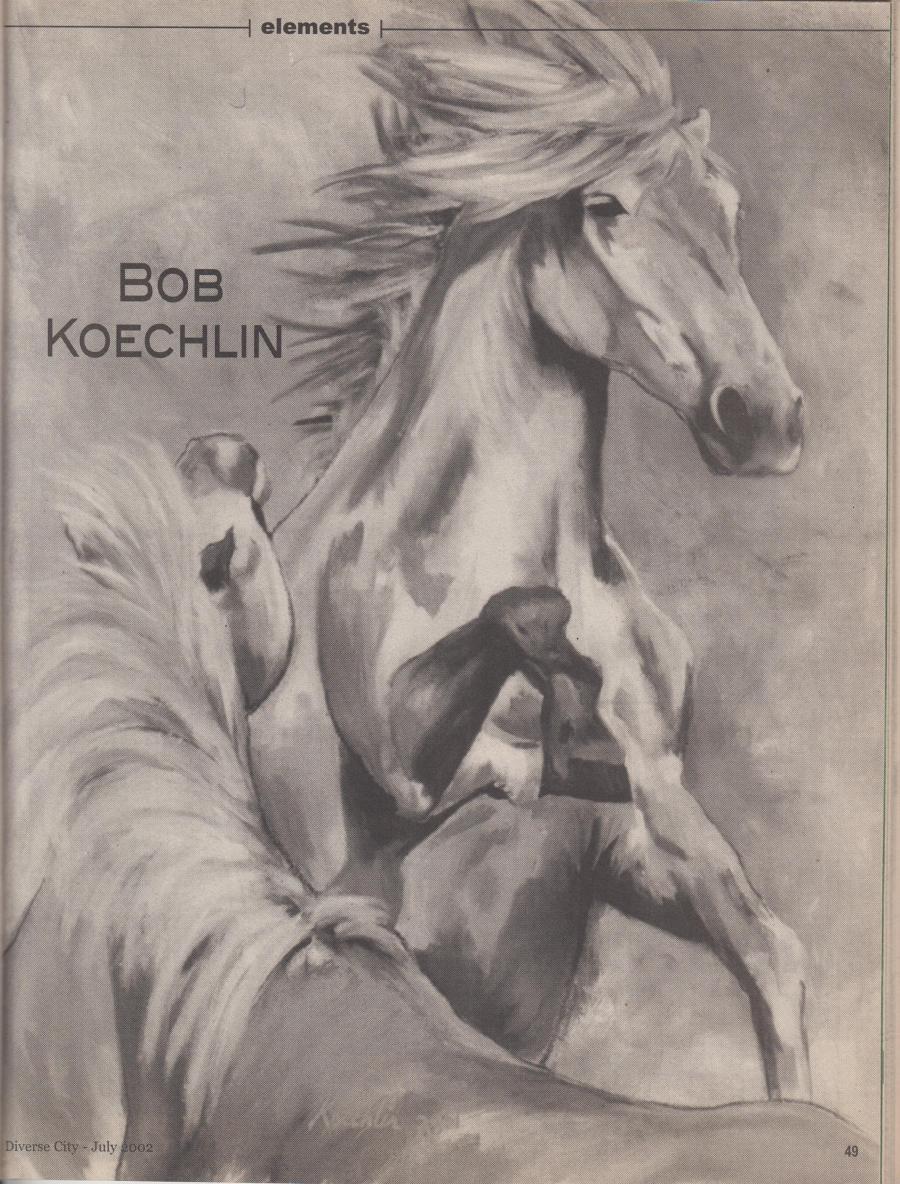

The local veterinarian calls Bryn Gerddes "Mother Theresa." She once brought a dying calf home from an auction to raise as a pet. The calf was shivering near the feed lot back-stage of the auction. Her body temperature was 87 degrees, as opposed to the normal 102. Gerddes couldn't stand to see the animal suffer. She put the little body into the passenger seat of the car, and brought her home where the calf convalesced in the laundry room under towels and hot water bottles for several weeks. A few years later, this calf is now a 400-pound cow who roams Gerddes pasture with several retired horses, and working horses which are ridden regularly.

But Gerddes is not just a good-Samaritan ranch-hand. She is also a tough competitor in seven events of the International Gay Rodeo Association (IGRA), as well as the chairperson of IGRA animal issues and concerns. As such, Gerddes has proposed near-zero-tolerance policies for rodeo infractions which endanger livestock. A minor first-time offense brings a warning. After that, it's disqualification.

Animal rights activists would argue that anyone actually concerned with animal welfare would not be involved with a rodeo, but would instead boycott or picket what is only a barbaric display of animal cruelty.

Animal rights activist Dan Shannon, campaign coordinator for People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA), would call Gerddes an animal abuser.

"Rodeo is an inherently abusive enterprise" says Shannon. "Rodeo events force animals to behave in ways which are unnatural to them. Horses don't jump like that unless they are in severe pain. Rodeos are plain and simple animal abuse for our amusement."

Gerddes discovered she had the heart of a cowgirl at the age of forty-five, when friends prompted her to compete in an IGRA event.

"One of the great things about gay rodeo," says Gerddes, "is that a person who has lived in New York city all their lives can compete in our rodeo." The contestants in gay rodeo are amateurs. Many have not roped or ridden much at all before their first time competing.

Officials at IGRA try to prepare contestants as best they can for what to expect, but some things must be experienced to be truly understood. A friend suggested to Gerddes that she might be good at "chute dogging." This is im event where a steer gets a little head start before the contestant runs after it and attempts to wrestle it to the ground. This event is a modified form of steer wrestling, which is traditionally done starting from the back of a horse, and jumping down onto the steer. It is a dangerous event which takes a high level of skill. Starting contestant and steer from ground-level in the chute softens the impact on both human and steer.

"I now understand how strong a steer is," says Gerddes. "You end up with 2oo pounds of steer, and less than 200 pounds of person on the ground. It's pretty challenging."

When asked about the danger to the steer of wrenching its neck like that, Gerddes says it's hard to describe the twisting action.

"It's more like trying to point their nose up. But I can say that in the six years I have been involved with IGRA, I have only seen one injury to a steer as a result of chute dogging."

"Break-away" calf roping is the IGRA's adapted version of traditional calf roping. In traditional calf roping, the contestant lassos the calfs neck and jumps down to hog-tie its feet, while his horse holds the rope taught. In IRGA calf roping, the end of the lasso rope is secured to the saddle with a very fine string. Once the calf is lassoed, and the running calf pulls the rope taught, the string breaks under the pressure, signaling the end of that round.

But to animal rights advocates, the intensity of an animal's physical discomfort isn't always the point. Calf-roping, in any form, is still "an example of violence and domination of man over animals" says Shannon. "The animals are still prodded and beaten in the chutes. And while there may be some modification in the specifics of the events, animals in the gay rodeo are no better off than animals in the traditional rodeo when they are out of the ring."

Most contestants in the IGRA just want to try something new with an element of the unknown attached.

"Most of the animals have never seen someone in drag before," says Gerddes. "They're surprised and curious. Being there gives you a whole different perspective. We try to make it fun for everyone, including the animals."

Outside of providing prize money for the contestants, and covering operating costs, all proceeds from the IGRA rodeo fun go to charity.

Shannon and PETA disagree about the "fun" part.

"We have protested rodeos, including the gay rodeo, many times," says Shannon. "What we find is that rodeos protest themselves. People watch the events and realize that they are supporting animal abuse. They leave telling us that they won't ever go back to a rodeo now that they know what's involved."

Shannon says the popularity of rodeo has steadily declined in recent years. "People realize that there are so many things we can do to amuse ourselves in non-violent ways. It's only a matter of time before rodeo phases out entirely."

Changing tone, Shannon adds a positive note, mentioning an animal-free gay human rodeo which took place in 1992. While Shannon did not attend the event personally, he describes it as more of a theatre piece based on rodeo, where people acted out the parts of the animals which would have been involved. He points to this as an example of a humane rodeo, much like the recent growing popularity of animal-free circuses.

From Bryn Gerddes perspective, the gay rodeo is a strong and growing tradition, where people get to interact with animals, not just watch. While she admits to the element of danger, she says it is minimized as much as possible for both human and animal contestants. Any injuries are generally minor, and the risk is worth the "incredible adrenaline rush" which cannot be matched by watching an interesting performance, or participating in some choreographed event.

IGRA Past, Present and Future

By A.J. Rogue

There's a reason for the similarities between the Imperial Court of The Rocky Mountain Empire and the International Gay Rodeo Association, other than the fact their names closely resemble each other. In fact, it's no fluke that there exists such an overlap of support between the two organizations. Not just an overlap, but an influence as well, as is evident by the fact that each organization is run by a royalty based structure. Not only that, the ICRME and the CGRA (the local association of the IGRA) are both huge fundraising organizations, raising thousands of dollars each year for various charities, gay and straight.

So how is it that these two organizations are so closely related? Simple. One was conceived by a member of the other.

In 1975, Phil Ragsdale, Emperor I of Reno, Nevada, came up with a new and creative way to help raise money for the community-organize a gay rodeo into a fundraising event. Ragsdale felt an amateur gay rodeo would be a fun way to raise money for the local Senior Citizens Annual Thanksgiving Day feed, and possibly erase some gay-stereotyping in the process. However, Ragsdale soon found it would not be easy to pull off the event. After much effort, he succeeded in landing the necessary site for the event, only to find resistance from local ranchers. Ranchers who didn't want a bunch of limp-wristed, amateur faggots using their livestock.

Undaunted, Phil proceeded to round up five "wild" range cows, ten "wild" range calves, one pig, and a Shetland pony, and, on October 2, 1976, held the first Gay rodeo. The event drew over 125 spectators.

In 1977, Ragsdale added even more twists to his rodeo fundraiser. First he founded the Comstock Gay Rodeo Association, thereby turning his entire project into the National Reno Gay Rodeo. Then, following the Imperial Court's lead, he added the "Mr. Miss, and Ms. National Reno Rodeo" contest, which raised $214.00 for the Muscular Dystrophy Association.

In 1980, the "Pacific Coast Gay Rodeo Association" began to emerge as one of the up and coming organizations, sending several talented rodeo contestants to the rodeo. Not only that, some of the top contenders for the Mr., Miss, and Ms. titles were coming from California and Utah.

Then, in 1981, it was the Lone Star State's turn. Texas came in with a bang, bringing in a hot contender for All-Around Cowboy, as well as strong contestants for the Mr., Miss, and Ms. contest. Miss Texas went on to win the "Miss National Reno Gay Rodeo" title that year, and the contest raised $40,000 dollars for MDA.

It was at the victory party that night that Wayne Jakino, now owner of Charlie's, (webmaster's note: Wayne managed Charlie's Denver, he did not own it) was challenged by the newly crowned "Miss" as to why there wasn't a better representation from Denver. To which Wayne replied: "Wait until next year!"

Jakino returned home full of determination and, with help, began to organize the Colorado Gay Rodeo Association. In just over one month, on September 13th, 1981, CGRA elected its first officers. Wayne Jakino was elected Founding President.

The first open membership drive occurred on December 1, 1981, and drew in 94 founding members. From there, the membership continued to steadily rise. Surprisingly, no one in this initial group even owned a horse. Still, remembering the verbal chiding he'd received at the hands of Miss Texas, Jakino vowed to return to Reno in force.

Ten months later, in August of 1982, Jakino made true his promise, descending on Reno with 270 CGRA members and over 150 supporters, all wearing shirts emblazoned with "Colorado Rides With Pride." They also brought with them the first mounted gay drill team, the Mile High Square Dancers, and the Denver Country Cloggers. Not only that, the 43 rodeo contestants they brought with them made up two-thirds of the contestants that year.

Things didn't stop there either. After traveling to Texas in 1982, in an unsuccessful attempt at getting them to start a rodeo, Wayne returned to Colorado, determined to lead the way by having Colorado host the first gay rodeo outside of Reno.

Although Jakino does confess to being a bit surprised, as were others in CGRA, about the fact that Denver was able to pull off its first rodeo when it did. "We really thought California's more open and bigger population would be a more positive base for such a thing," he said. "We also thought that about Texas. In fact we went to Texas to beg them to put on a rodeo, but apparently we went to the wrong city first. Apparently, there are some weird boundary issues between Houston and Dallas when it comes to gay things, and we ended up losing some support by going to Houston first, instead of Dallas.

So, instead of Texas holding a rodeo, they promised to organize their own association, and to support us if we threw a rodeo. So we came home to Denver to do just that." He soon found out, however, that doing so would not be easy.

"It wasn't that people were coming out and outright refusing us the use of their land," Jakino said. "They were much more politically correct in the way they did it. For example, Jefferson county, where we now hold our rodeo, told us at first; 'Sure, we'd be happy to book your event!' Only, there didn't seem to be a date available. For the next ten years. It finally took a lawyers intervention before Aurora offered us the use of a run-down arena on the outskirts of town."

Finally, on July 3, 1983, the Rocky Mountain Regional Rodeo held its first ever event. Texas, as they'd promised, turned out in large numbers to support the event. The following year, in 1984, the Texas Gay Rodeo Association was born.

Now, with other states rapidly organizing rodeos, and more and more contestants joining each day, Jakino felt it was time to put together an umbrella organization that would provide unity between the rodeos, as well as standardization for the contestants. Leaders from Colorado, Texas, California and Arizona were invited to Phoenix for a preliminary discussion. Jakino went as one of the Colorado delegates. It was there, at this initial meeting that all agreed to proceed with the umbrella organization.

The four associations met again in March of 1985, this time in Denver, to file the Articles of Incorporation for the International Gay Rodeo Association," and to elect a temporary board. To his utter surprise, Jakino found himself accepting the position as president of IGRA.

"Not many people know this about me," he said, "but I'm absolutely terrified of speaking in front of crowds. I do alright in front of a few people, but get me in front of a large group and I go to pieces. This was especially true when I ran for IGRA president. I break out into a huge sweat, I have cotton mouth, and I'm terrified. It takes me a few minutes to hit my stride, and then look out! I don't shut up!" he laughed.

As with any organization, IGRA has had its ups and downs.

While it has grown in some areas of the country, other areas have been unable to keep their associations alive. Still, the IGRA continues to thrive in this day of advanced technology and fierce competition among gay organizations for membership.

"There have been a lot of changes in the 20-some-odd years we've been around," Jakino said. "Especially here in Denver. For example, last year, Jefferson County came to us and asked us to stage our rodeo there. We didn't have to beg them, like the first year. Also, I remember the Denver Convention Bureau taking us out to the Stock-show arena the first or second year we wanted to put on a rodeo, for the purpose of offering us the use of the arena. Only they did so at an ungodly price. Ten years ago, when we wanted to stage our tenth anniversary rodeo, we quietly went over to the arena and told them this would be our tenth, and we'd love to have a nice indoor arena to stage it in. This time, they agreed to let us use the facility, for about half what they'd originally asked that first or second year."

Jakino credits this change in attitude to the fact that the organization, over the years, has gained the respect of the straight rodeo circuit. "Our sub-contractors-the ones who provide us with the livestock we use in the rodeos-usually come in with the attitude that they're dealing with a bunch of rank amateurs," he explained. "However, by the end of the weekend, they generally seem to respect us for what we do, and how sincere we are about it. So little by little, we've earned their respect. We've also been instrumental helping formulate some of the vocabulary that is used to re-educate the animal rights groups, like PETA, in how our animals our used."

"It's amazing how many doors the rodeo has opened up for myself, and for IGRA, both here and across the nation," Jakino continued. "Everyone is still shocked that gays and lesbians would even be involved with a rodeo. It isn't something they associate with us. The rodeo lends support to the fact that we truly are everywhere."

"Not only that," Jakino went on, forgetting, for the moment, his fear of speaking, "We're the only national gay organization that I know of to succeed in obtaining national sponsorship. Not once, but four times, from such companies as Miller and Budweiser."

When asked whether or not he felt there was a future for gay rodeo, and the IGRA in particular, Jakino had this to say: "I believe it will continue this growth factor-this insurgence we're seeing. Our ultimate next step in growth is to create smaller organizations. As opposed to the Colorado Gay Rodeo Association, for example, I'd like to see the Mile High City Gay Rodeo Association. That would allow Colorado Springs to form their own association. That would help keep our membership in place."

As far as whether or not he ever plans on retiring from the rodeo circuit, Jakino couldn't tell me. "Every year I tell them 'this is it, my final year.' Yet it seems I have a hard time saying no. I keep saying I'm gonna pull back, I keep saying I'm gonna pull back..." he repeated, laughing. "Seriously, it's hard to walk away from something you've been so passionately involved with for twenty-one years. As I said, IGRA opened a lot of doors for me, and for gay people in general. And continues to do so."

One need only look at the numerous things Wayne Jakino has done, and still does, for IGRA and for our community, to realize the truth in this statement. For the sake of our community and the thousands of dollars that has been raised, we should all hope that he and the IGRA ride on forever.

Ty Teigen

Ty Teigen has been riding horses since she was two years old.

A software engineering manager at JD Edwards, Teigen has been involved with gay rodeo for seven years. But she is no stranger to the western way of life. "I'm kind of the oddball of the group," she says. "I started rodeoing when I was eight years old. I grew up doing that. My family got into horses when I was little...junior rodeo, I did that from when I was eight until I was 18."

It was after she turned eighteen that a number of circumstances took Teigen away from the rodeo for 12 years.

"My parents got a divorce and sold everything, and that's ahout the time that I came out. I didn't see a way for it (being gay and being in rodeo) to work together so I gave it up. Traditipnal rodeo is so heterosexual and homophobic. So I gave it up and moved to Denver."

Although she says that her decision to quite rodeo was based more on her parent's divorce and the selling of the family ranch then traditional rodeo's bigotry, it was a decision nonetheless that was filled with regret.

"There wasn't a day in my life that I didn't miss it. Once you've got horse fever it never goes away."

It was when Teigen was living in Denver that rodeo unexpectedly came back into her life.

"I met two girls who were involved in the rodeo and I started hanging out with them because they have horses and they train and have their own facility," she says. "They (let) me ride their horses. And they brought me to my first gay rodeo in Denver, and they said 'here, ride. our horse,' and they let me get back involved and it was really nice. And then a year later I graduated from college and bought my own horse."

That was eight years ago. And she has been rodeoing ever since. This is the first year Teigen has traveled on the circuit. And she plans to compete in five rodeos including Denver-and hopefully finals.

Teigen says she is proud of the way gay rodeo has evolved over time.

"Gay rodeo has done a really good job and improved over the seven years that I have been involved. The level of skill has increased so much. I see an awful lot of people in the gay rodeo who can win straight rodeo-absolutely."

She says she wants those who attend the rodeo to see gay rodeo for what it really is:

"What I want them to mostly see is that it's fun and to enjoy it. The partnership between the horse and the rider is something that I think is amazing and that's what draws me in."

It is this partnership that really draws her to rodeo.

"I have a thousand-pound animal that trusts me completely. We are friends. Horses have personalities like dogs and cats-they're all individuals. Different horses match or don't match your personality. The one that I have now absolutely matches my personality better than any horse I've ever known. We totally get each other. It's just cool. When you're out there and you lift your hand and move your leg and the horse responds and does exactly what you ask it to do at a high rate of speed-the trust is not only the horse trusting you that you're not going to put them in a situation where they're going to get hurt, but also you trust that animal to go at a really high rate of speed and that you're not going to fall down and you're not going to get hurt."

Teigen has had a lot of memorable rodeo experiences over the years. But her highest achievement came just a year ago at the Denver rodeo when she won the belt buckle for breakaway calf roping.

"That is by far and away my favorite event. I love to rope more than anything," she says. "When I was a kid I used to do that a lot. And I had been struggling with finding a horse that was good to rope on and follow cows, and my horse just worked really well for me-better than he should have because he's never been trained really well because I don't have access to cows. It just meant a lot to me, more than anything else at that point. And to have done it here in Denver in front of my friends was extra special.

"But to me just being at a rodeo-every bit of it is good. There are no bad moments. It's like being a teen-ager again."

Ken Pool

Colorado Gay Rodeo Association President Ken Pool was living in West Hollywood when the rodeo bug bit him.

Pool, who grew up in the small town of Tomball outside of Houston, Texas had always been around horses, but had never participated in a rodeo before.

"When I was sixteen I felt like being gay and being a cowboy was not going to be compatible. And that I couldn't pursue both. So I gave up the horses and really missed it," Pool says.

"But when I was living in West Hollywood I was going to a county bar and a group of us got together to go to a rodeo in Phoenix-this gay rodeo we heard about. And we traveled over to Phoenix and all my buddies spent their time in the dance tent area watching the dancers and I watched the rodeo and thought 'you know? I could do this."

Pool attended a buck out, which is a practice rodeo, rode a steer, shoot dogged, and started his gay rodeo career. "I was twenty-seven or twenty-eight. I wasn't young."

That was fourteen years ago.

"I never went to another rodeo again that I didn't compete."

It was only two weeks after the buck out that Pool was competing in gay rodeo, a fete which might seem amazing to some, but to Pool it was just something that he felt compelled to do.

"I learned and added events as I went along."

Pool started with rough stock, riding steers then graduated to riding bulls and shoot dogging, and the camp events. For the Denver rodeo Pool plans to do ten of the thirteen events.

"I'm going to steer ride for the first time in four years," he says. "I don't always do that many events. If I go to a rodeo and I can't take my horse and I fly in, I will go and just do shoot dogging and enjoy the rodeo. That's the least I have done. And I've done that more this year then in years past."

Part of his decline of event participation, Pool says, is because he has gotten more involved with the political side of CGRA. But it is the rodeo, Pool says, where his heart really belongs.

"I love the competition-which is probably not the first part I am a bit competitive by nature and I enjoy that. Even though it's not all about the winning it's about doing your best. But added to that, there is a great deal of freedom in gay rodeo. I can compete in this sport that is something I love with someone who I love and not be embarrassed by it. If I have a great run or a great ride and I can come out and share that with my lover, that's a nice place to be."

"I've also competed in other venues or associations that are straight oriented, and it's not that there's necessarily discrimination-although there certainly is-and there are a lot of gay people that compete in straight rodeo, even pro rodeo, but they pretty much have to stay closeted in order to get along. I don't think you'll find anyone who competes in the gay circuit that is doing it for the money. It's not there."

What is there, however, is a much deeper sense of mission.

"Why I have now gotten more involved with gay rodeo-what keeps me in it-we have a sense of responsibility, or should have-and for me growing up, if I had known about people like me now, and others who are in the association, it would have made my transition much, much easier. I would not have given up horses. I would have kept on rodeoing and enjoying it, and realized that I could do that because there were examples of it."

Coupled with this deeper sense of mission is the romantic notion of life on the range and the cowboy way of life that has enticed many a child since they were old enough to dream about riding off into the sunset. For Pool, this is an ideal that is still very much alive and well.

"I want to live that romantic cowboy way of life. It's not realistic for me to rodeo for a living but I will work to support my rodeo habit. And the romantic side of that is yes-I'm in love with a cowboy, and he loves rodeo, too. I spent a lot of my youth coming out and living in cities, gay ghettos, as it were. And I would prefer that my neighbors all know that I'm gay and don't care. They're more concerned with how I ride my horse.

"When I go rope with neighbors and we do prayer meetings afterwards, they don't look down their nose at me. They're more concerned about did I catch my steer."