A Gay Dallas Cowboy Looks for Life's Rhythm -

and Finds It

By Stephen R. Underwood

TRIANGLE Co-Editor

About eight miles southeast of downtown Dallas, Wade Earp walked outside his back door to a rising sun one Saturday morning into the crisp, northern air to start a daily ritual. The ducks, geese and guineas - some seventy-five in all - that inhabit his ranch are hungry. And they let him know it. In particular, the geese are the loudest. They honk and hiss with irritable persistence at both the notion of getting fed and fending off a reporter. The geese are also the bullies of the block, hoarding over the spread of feed Earp scatters as if they had just returned from a dip in a gold-plated pond reserved for Caesar's flock.

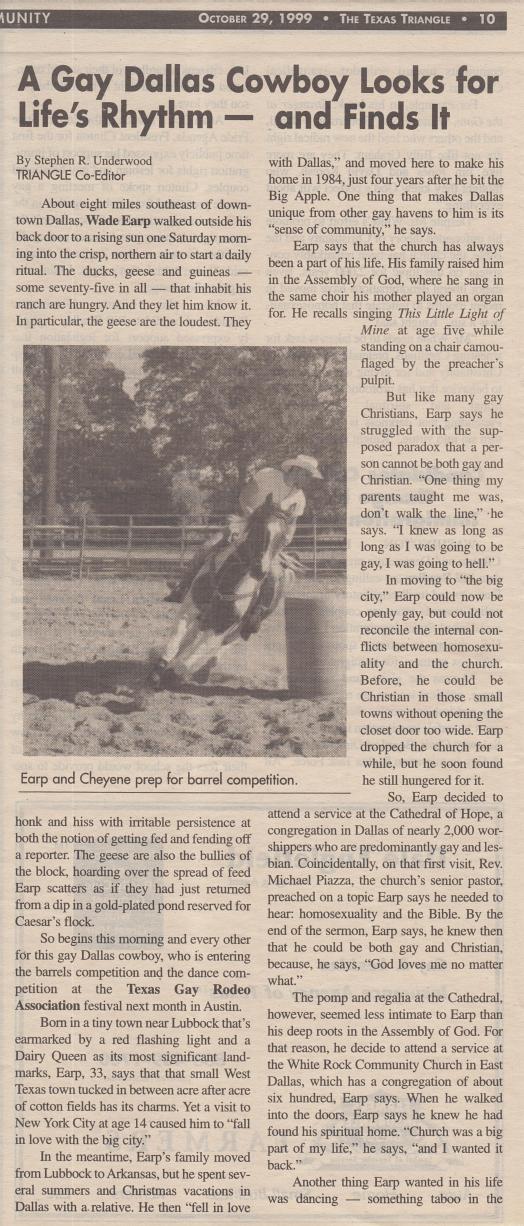

So begins this morning and every other for this gay Dallas cowboy, who is entering the barrels competition and the dance competition at the Texas Gay Rodeo Association festival next month in Austin.

Born in a tiny town near Lubbock that's earmarked by a red flashing light and a Dairy Queen as its most significant landmarks, Earp, 33, says that that small West Texas town tucked in between acre after acre of cotton fields has its charms. Yet a visit to New York City at age 14 caused him to "fall in love with the big city."

In the meantime, Earp's family moved from Lubbock to Arkansas, but he spent several summers and Christmas vacations in Dallas with a relative. He then "fell in love with Dallas," and moved here to make his home in 1984, just four years after he bit the Big Apple. One thing that makes Dallas unique from other gay havens to him is its "sense of community," he says.

Earp says that the church has always been a part of his life. His family raised him in the Assembly of God, where he sang in the same choir his mother played an organ for. He recalls singing This Little Light of Mine at age five while standing on a chair camouflaged by the preacher's pulpit.

But like many gay Christians, Earp says he struggled with the supposed paradox that a person cannot be both gay and Christian. "One thing my parents taught me was, don't walk the line," he says. "I knew as long as I was going to be gay, I was going to hell."

In moving to "the big city," Earp could now be openly gay, but could not reconcile the internal conflicts between homosexuality and the church. Before, he could be Christian in those small towns without opening the closet door too wide. Earp dropped the church for a while, but he soon found he still hungered for it.

So, Earp decided to attend a service at the Cathedral of Hope, a congregation in Dallas of nearly 2,000 worshippers who are predominantly gay and lesbian. Coincidentally, on that first visit, Rev. Michael Piazza, the church's senior pastor, preached on a topic Earp says he needed to hear: homosexuality and the Bible. By the end of the sermon, Earp says, he knew then that he could be both gay and Christian, because, he says, "God loves me no matter what."

The pomp and regalia at the Cathedral, however, seemed less intimate to Earp than his deep roots in the Assembly of God. For that reason, he decide to attend a service at the White Rock Community Church in East Dallas, which has a congregation of about six hundred, Earp says. When he walked into the doors, Earp says he knew he had found his spiritual home. "Church was a big part of my life," he says, "and I wanted it back."

Another thing Earp wanted in his life was dancing - something taboo in the AOG. "I was raised that you didn't dance," he says. Still, Earp remembers that his younger brother was his first dance partner. The pair would wait for the parents to leave, then play music and hop around. They first danced to Rockin' Robbin.

That love for dance carried through to his adult life. Today, Earp teaches advanced country and western dance lessons on Wednesday nights in Dallas at the RoundUp, a popular gay bar on Cedar Springs Rd. He also teaches private lessons there on Monday through Thursday nights, as well as assisting Juanita Bemel, another dance instructor, with beginning dance lesson on Tuesday and Thursday nights.

Another Kind of Dance

Earp met Jackie Riley at the church in 1993, a man he would date then settle down with and dance with at the Round-Up. The pair had eyed each other for weeks, Earp says. Then it became, "Hello." Then, "Hello, how are you doing." Then, finally, Earp asked him to dance one night at the Round-Up. The dance evolved into a relationship, and the new couple moved in together at an Oak Lawn townhouse.

Besides living and dancing together, Earp and Riley worked together as well. The paramours traveled the United States attending gift shows selling a line of Mexican pewter while working at a local gallery.

Just before a January 1997 trip to an Arkansas show, however, Riley became incredibly ill. Thinking at first he had food poisoning, Riley went on the trip and was sick the whole time.

When the couple planned a second trip to Arkansas a month later, Riley stayed home. Earp went on to a gift show to make a planned delivery. But he would soon get a call that Riley was admitted to Parkland Hospital with a severe kidney infection. Earp would also learn for the first time that Riley was HIV positive.

Clearly, Earp says, it was a time he needed his family most. Riley declined rapidly, dropping his weight into the low 120's in large part because he could not eat. Like many people needing assistance, taking care of Riley was a full-time job, which required attention in addition to a busy work schedule. Eventually, Earp says, he was convinced to let family and friends help with Riley's care. Someone told him that he was robbing other people of a blessing by trying to do it all himself.

Earp says his mother, Doris Earp, who lives in Arkansas, proved to be an incredible source of strength, even though she wasn't at all comfortable with homosexuality in general or with Earp's relationship with Riley in particular.

Still, as Riley lay in his hospital bed, he expressed doubts about his own salvation, Earp says. Could it be true that God didn't like gays and he would not see the gates of Heaven? 0r was the preaching at White Rock true, that you can be gay and God still love you?

Earp enlisted his mother's help to calm Riley's fears. Calling her on a Sunday in April 1997, she traveled straight to Dallas from Little Rock to be by Riley's side. There she would assure him that he would indeed go to Heaven when he died, Earp says. And after staying up with Riley all night, Mrs. Earp left Dallas to be back at work Monday morning. Riley died April 30, 1997 and was laid to rest after a service at White Rock.

"Losing a spouse, it teaches you to look at life a lot different," Earp says. "I'm glad the church was there for me when Jackie got sick."

More Dreams After the Nightmare

Two-and-a-half years after his lover's death, Earp picked up the pieces of his life and went on to realize another dream: owning his own ranch property with an arena, where he could train his prized horse, Cheyene, for barrels competition. Through the help of a friend, Earp found an L-shaped four-acre lot in Southeast Dallas with a two bedroom two-bath house. He is restoring the house with a Santa Fe flair. Inside the house, pictures of friends pepper the walls, each having its own story, Earp says. Close by, one part of a wall displays awards from TGRA dance competitions.

Outside in back of the lot, a medium size pond plays host to migratory ducks and the giddy geese. Near there, a small storage shed with five stalls houses the coveted feed for both the birds and the horses. Further back, a lighted competition-style arena with a cow shoot waits for the day's training. Despite its rustic appearance, it is an individual world married with modernity: the classic country life of a quintessential Texan - the horses, the animals, the house - and the usual moden conveniences - the cell phones, the satellite dish, the big, black Dodge truck - all wed to weave a unique lifestyle.

On this particular day, Earp has his work cut out for him. First, he waits for a friend who owns a lawn service to drop off a tractor. When it arrives, Earp attaches an 18 blade disc contraption at the tractor's end and chums the semi-grassy arena until the dust looks like chocolate cake mix. After that, a device called a drag replaces the discs. It smoothes the soil even more, and will allow Cheyene to dig in and execute the turns around the barrels with more precision. And even though the day is cool and temperatures hover in the mid 60s, the work is still hot and dirty. The job takes nearly an hour and a half.

It will be after all this, though, that Earp and horse trainer Destry Fleming, 32, go over the day's barrel training for Cheyene. The 17-year-old horse is a large one - sixteen hands, and Fleming is quick to notice that Cheyene is shaping up well from weeks of training. (Consequently, it is believed, but not confmned, that the first rodeo took place in Cheyenne, Wyo. in 1872.)

Fleming instructs Earp to work the horse in clock-wise circles. He is looking for the point when Cheyene settles down and executes the spinning gaits in a relaxed manner. On the third round of spinning in circles, Cheyene appears to reach a symmetrical gait, and Fleming is pleased. The horse is now breathing hard and breaking a sweat. The direction is then reversed, and afterwards the horse cools down a bit. "He's got some spunk today," Earp says, leaning over to tell Fleming.

Returning to barrel training after a short absence, Fleming lives in Fort Worth and plans to get back into competition himself. Rodeos are big business, he says, as some prizes for top winners in the straight rodeo circuit eclipse $1 million. Most of that money will be needed to maintain a high caliber barrel racing horse, he says, since most can cost between $25,000 and $100,000, not including vet care. "Barrel racing is an art form," Fleming says. "If you don't specialize, you won't win."

Earp gets set for barrel training. Fleming posts three blue barrels in the center of the arena and plants them like points of an equilateral triangle. He wants the horse to execute several practice runs to see what is remembered from previous training. As Cheyene bolts out of the far end of the arena and races to the first barrel, Fleming is not pleased by the way the horse swings its rear in anticipation of negotiating the turns around the barrel. He then instructs Earp to loosen the right rein just a bit. That helps, but Cheyene gets excited by the practice and seems to swing even more.

Fleming then instructs Earp to slow Cheyene down just as he approaches each barrel. He pays special attention to the position of the horse's nose as it circles the barrel. After several practice runs, Cheyene completes a tight set in the manner Fleming wants. Fleming tells Earp to stop at that point so the training really "sinks in."

Several nights a week, Earp returns to the arena to practice after weekly dance lessons. He does so at that time because he works during the day. On one occasion, he chased away the neighborhood skunk, which he found twaddling away in the middle of the dark arena.

After the training, it's wash time for Cheyene. The horse is unsaddled and soaked with water, then shampooed and conditioned. Fleming helps with the wash down, but he has other concerns: he is eyeing a horse put up for sale by Earp's neighbor. He thinks he has a friend who may buy it. Failing to find the neighbor, Fleming wonders aloud if the seller is inside a trailer next to the house "snaking on Little Debbie's." Fleming leaves to fmd out. Earp then jokes: "Two things get Destry going: men and horses."

Earp says that dancing and horse riding have at least one thing in common: a rhythm. "You feel it when you're dancing, when two people become one," he says. "It's like a dance, too, when you're riding and you and your horse are one."

Whether he wins in Austin or not, Earp has two other wishes: he would like his mother to recite the prayer for the opening ceremonies of the gay rodeo; and he would also like her to attend his dance competition. But the latter may be hampered by his parent's unfavorable impression of nightclubs, Earp says, fed in part by their conservative leanings in the church. Earp hopes that his family will be able to convince his parents that attending the competition doesn't mean they have to approve of other people's lifestyles. Even so, since Riley's death, Earp says his parents and his family have "come a long way" on other issues.

As the sun sets, Earp lights a barbecue pit and goes into his kitchen to tenderize steaks and chicken breasts in preparation for several guests arriving later for dinner. Green beans and kernel com simmer on the stove, and a loaf of garlic bread warms in the oven below. A Boston Creme pie awaits its sacrifice. As Earp walks outside into the chilly air, he lays the steaks and chicken breasts inside the pit. The charcoal crackles in anticipation of a good reward for a hard day's work, just one in the life of this gay Dallas cowboy. And the geese, finally, are quiet.