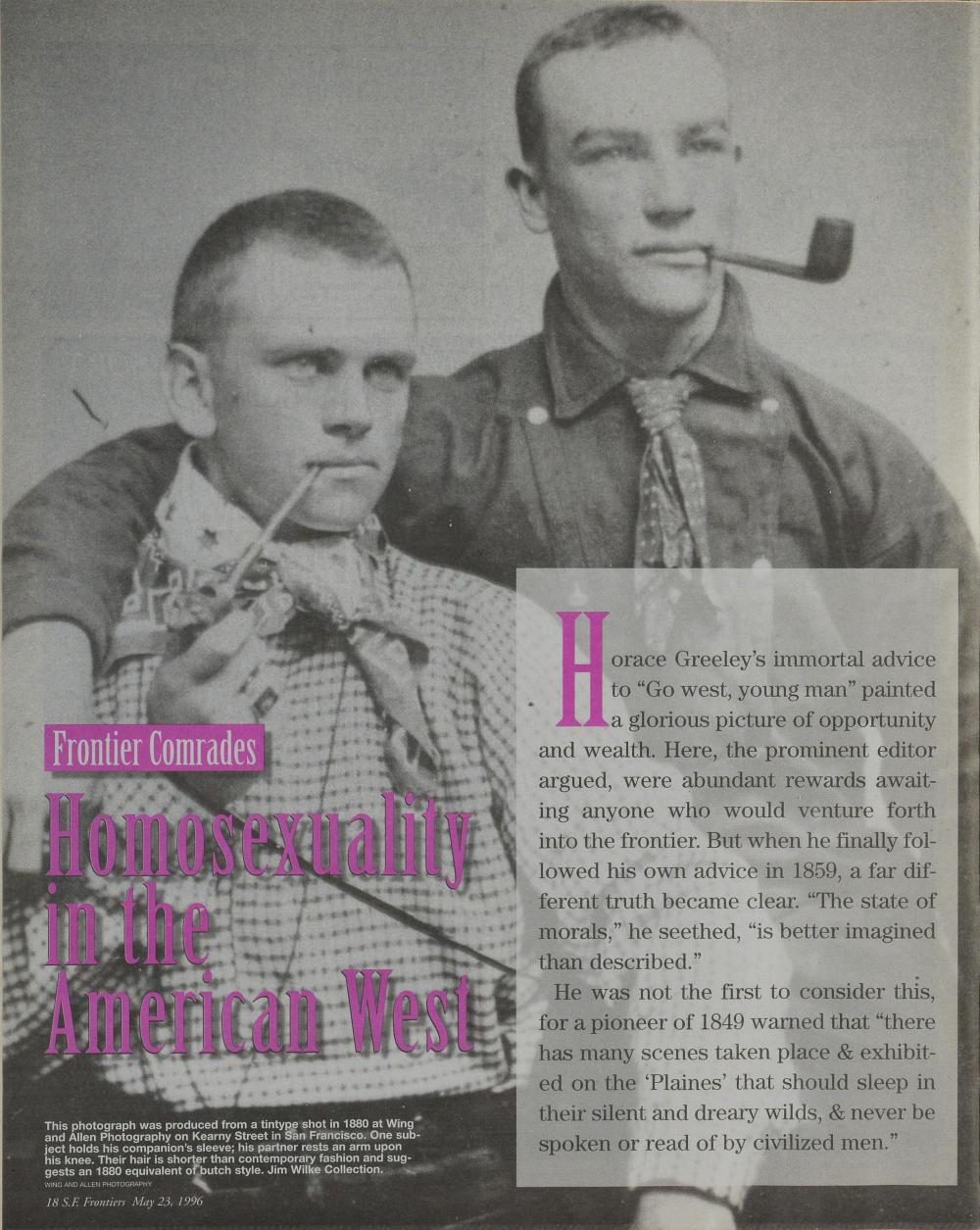

Homosexuality in the American West

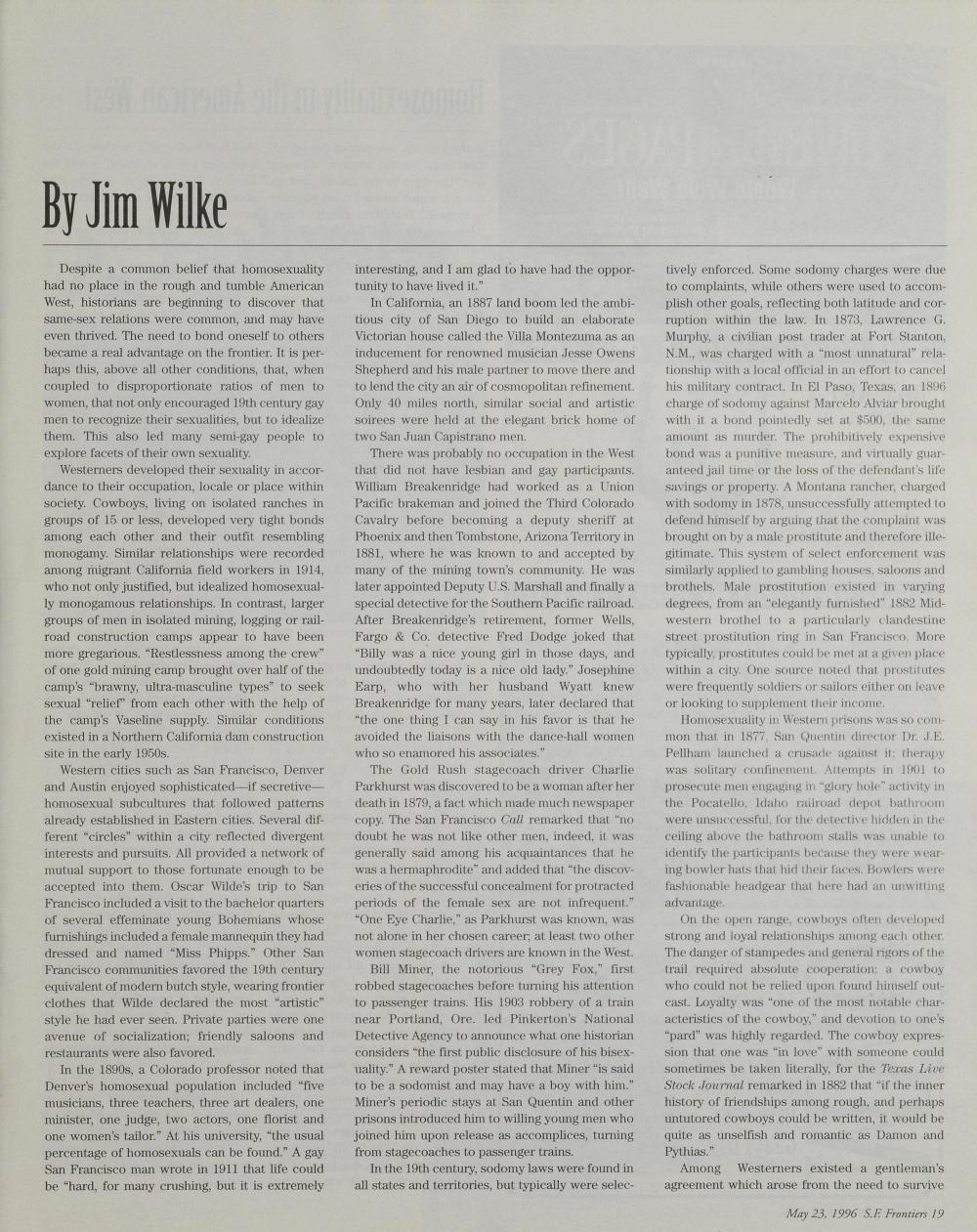

(Description of photograph)

This photograph was produced from a tintype shot in 1880 at Wing and Allen Photography on Kearny Street in San Francisco. One subject holds his companion's sleeve; his partner rests an arm upon his knee. Their hair is shorter than contemporary fashion and suggests an 1880 equivalent of butch style. Jim Wilke Collection.

By Jim Wilke

Horace Greeley's immortal advice to"Go west, young man" painted a glorious picture of opportunity and wealth. Here, the prominent editor argued, were abundant rewards awaiting anyone who would venture forth into the frontier. But when he finally followed his own advice in 1859, a far different truth became clear. "The state of morals," he seethed, "is better imagined than described."

He was not the first to consider this, for a pioneer of 1849 warned that "there has many scenes taken place & exhibited on the 'Plaines' that should sleep in their silent and dreary wilds, & never be spoken or read of by civilized men."

Despite a common belief that homosexuality had no place in the rough and tumble American West, historians are beginning to discover that same-sex relations were common, and may have even thrived. The need to bond oneself to others became a real advantage on the frontier. It is perhaps this, above all other conditions, that, when coupled to disproportionate ratios of men to women, that not only encouraged 19th century gay men to recognize their sexualities, but to idealize them. This also led many semi-gay people to explore facets of their own sexuality.

Westerners developed their sexuality in accordance to their occupation, locale or place within society. Cowboys, living on isolated ranches in groups of 15, or less, developed very tight bonds among each other and their outfit resembling monogamy. Similar relationships were recorded among migrant California field workers in 1914, who not only justified, but idealized homosexually monogamous relationships. In contrast, larger groups of men in isolated mining, logging or railroad construction camps appear to have been more gregarious. "Restlessness among the crew" of one gold mining camp brought over half of the camp's "brawny, ultra-masculine types" to seek sexual "relief' from each other with the help of the camp's Vaseline supply. Similar conditions existed in a Northern California dam construction site in the early 1950s.

Western cities such as San Francisco, Denver and Austin enjoyed sophisticated, if secretive, homosexual subcultures that followed patterns already established in Eastern cities. Several different "circles" within a city reflected divergent interests and pursuits. All provided a network of mutual support to those fortunate enough to be accepted into them. Oscar Wilde's trip to San Francisco included a visit to the bachelor quarters of several effeminate young Bohemians whose furnishings included a female mannequin they had dressed and named "Miss Phipps." Other San Francisco communities favored the 19th century equivalent of: modern butch style, wearing frontier clothes that Wilde declared the most "artistic" style he had ever seen. Private parties were one avenue of socialization; friendly saloons and restaurants: were also favored.

In the 1890s, a Colorado professor noted that Denver's homosexual population included "five musicians, three teachers, three art dealers, one minister, one Judge, two actors, one florist and one women's tailor." At his university, "the usual percentage of homosexuals can be found." A gay San Francisco man wrote in 1911 that life could be "hard, for many crushing, but it is extremely interesting, and I am glad to have had the opportunity to have lived it."

In California an 1887 land boom led the ambitious city of San Diego to build an elaborate Victorian house called the Villa Montezuma as an inducement for renowned musician Jesse Owens Shepherd and his male partner to move there and to lend the city an air of cosmopolitan refinement. Only 40 miles north, similar social and artistic soirees were held at the brick home of two San Juan Capistrano men.

There was probably no occupation in the West that did not have lesbian and gay participants. William Breakenridge had worked as a Union Pacific brakeman and joined the Third Colorado Cavalry before becoming a deputy sheriff at Phoenix and then Tombstone, Arizona Territory in 1881, where he was known to, and accepted by many of the mining town's community. He was later appointed Deputy U.S. Marshall and finally a special detective for the Southern Pacific railroad. After Breakenridge's retirement, former Wells, Fargo & Co. detective Fred Dodge joked that "Billy was a nice young girl in those days, and undoubtedly today is a nice old lady." Josephine Earp, who with her husband Wyatt knew Breakenridge for many years, later declared that "the one thing I can say in his favor is that he avoided the liaisons with the dance-hall women who so enamored his associates."

The Gold Rush stagecoach driver Charlie Parkhurst was discovered to be a woman after her death in 1879, a fact which made much newspaper copy. The San Francisco "Call" remarked that "no doubt he was not like other men, indeed, it was generally said among his acquaintances that he was a hermaphrodite" and added that "the discoveries of the successful concealment for protracted periods of the female sex are not infrequent." "One Eye Charlie," as Parkhurst was known, was not alone in her chosen career; at least two other women stagecoach drivers are known in the West. Bill Miner, the notorious "Grey Fox," first robbed stagecoaches before turning his attention to passenger trains. His 1903 robbery of a train near Portland, Ore. led Pinkerton's National Detective Agency to announce what one historian considers "the first public disclosure of his bisexuality." A reward poster stated that Miner "is said to be a sodomist and may have a boy with him." Miner's periodic stays at San Quentin and other prisons introduced him to willing young men who joined him upon release as accomplices, turning from stagecoaches to passenger trains.

In the 19th century, sodomy laws were fond in all states and territories, but typically were selectively enforced. Some sodomy charges were due to complaints, while others were used to accomplish other goals, reflecting both latitude and corruption within the law. In 1873, Lawrence G. Murphy, a civilian post trader at Fort: Stanton, N.M., was charged with a "most unnatural" relationship with a local official in an effort to cancel his military contract. In E1 Paso, Texas, an 1896 charge of sodomy against Marcelo Alviar brought with it a bond pointedly set at $500, the same amount as murder. The prohibitively expensive bond was a punitive measure, and virtually guaranteed jail time or the loss or the defendant's life savings or property. A Montana rancher, charged with sodomy in 1878, unsuccessfully attempted to defend himself by arguing that the complaint was brought on by a male prostitute and therefore illegitimate. This system of select enforcement was similarly applied to gambling houses, saloons and brothels. Male prostitution existed in varying degrees, from an "elegantly furnished" 1882 Mid-western brothel to a particularly clandestine street prostitution ring in San Francisco. More typically, prostitutes could be met at a given place within a city. One source noted that prostitutes were frequently soldiers or sailors either on leave or looking to supplement their income.

Homosexuality in Western prisons was so common that in 1877, San Quentin director Dr. J.E. Pellham launched a crusade against it: therapy was solitary confinement. Attempts in 1901 to prosecute men engaging in "glory hole" activity in the Pocatello, Idaho railroad depot bathroom were unsuccessful, for the detective hidden in the ceiling above the bathroom stalls was unable to identify the participants because they were wearing bowler hats that hid their faces. Bowlers were fashionable headgear that here had an unwitting advantage.

On the open range, cowboys often developed strong and loyal relationships among each other. The danger of stampedes and general rigors of the trail required absolute cooperation: a cowboy who could not be relied upon found himself outcast. Loyalty was "one of the most notable characteristics of the cowboy," and devotion to one's "pard" was highly regarded. The cowboy expression that one was "in love" with someone could sometimes be taken literally, for the Texas Live Stock Journal remarked in 1882 that "if the inner history of friendships among rough, and perhaps untutored cowboys could be written, it would be quite as unselfish and romantic as Damon and Pythias"

Among Westerners existed a gentleman's agreement which arose from the need to survive in the frontier. One part of this agreement was mutual respect, allowing one "the right to live the life and go the gait which seemed most pleasing to himself." This frontier code of conduct allowed many people to enjoy open relationships that would otherwise not have been possible.

Many circumstances contributed to personal closeness on the ranch and trail. Cowboys frequently bedded in pairs with their "bunkie," and the ranch bunkhouse was occasional called a "ram pasture." Many cowboys engaged in "mutual solace," a tender, expressive and euphemistic term for sexual relations. Vulgar and explicit "ugly songs," as they were known in Arizona, boasted of sodomy, virility and phallic size around a campfire. Other songs, like "The Open Ledger," castigated "cocksmen":

Count the cocksman from Colorado,

Where Pike's Peak ponders and broods.

A miner, a mucker, the phony cocksucker,

and his racket is wranglin' dudes.

He sponsors a double-rigged saddle;

his gifts are gifts of the gab;

With a rope made of grass and teeth in his ass,

the best he can get is the tab.

Colorado newspapers were full of lesbian and gay elopements. In 1889, the small farming town of Emma, a wide spot in the road a few miles away from the silver mining town of Aspen, was "rent from the center to circumference" over the "sensational love affair between Miss Clara Dietrich, postmistress and general storekeeper, and Miss Ora Chatfield." The Aspe Times noted with wonder about the relationship, which grew "out of the apparently insane infatuation of one woman for another," for love letters written between them caused the Denver papers to remark that the "love which existed between the two parties was of no ephemeral nature, but as strong as that of a strong man for his sweetheart." Despite attempts by their families and the Aspen sheriff to separate them, the "lady lovers" successfully eloped. In Denver, newspaper reporters "searched the city in all directions, but without finding any trace of the missing couple" and it was assumed that they had lit off elsewhere. "If the case ever comes to court," wrote the Denver Times," from a scientific standout alone it will attract widespread attention."

In 1898, Boulder teamster W.H. Billings left his wife and sold the horses from which he made his living in order to run away with Charles Edwards, an itinerant saloon entertainer who made his living playing the banjo and performing acrobatics. Billings bought him a drink and was soon "in love" with his discovery. A Denver newspaper reported that Billings was "not happy unless he was trailing around the streets with Edwards" and that ''if his home had any charms for him, said his wife, they had fled and all on account of a banjo player."

In the Rocky Mountain mining town of Trinidad, Charles "Frenchy" Vobaugh was well known for his restaurant's fine dining. Less well known was that both he and his wife of 30 years were women. Many women assumed the outward appearance of heterosexual couples in order to marry, work and vote-prerogatives of citizenship otherwise denied them by Victorian society. It was a dangerous yet rewarding strategy, embraced by brave women who possessed a strong sense of self-determination. Oregon native Lucile Hart, a Stanford Medical School graduate, is noted by historian Jonathan Katz to have dressed as a man in order to marry the woman she loved. Her own doctor wrote that "if society will but leave her alone, she will fill her niche in the world and leave it better for her bravery."

The Western frontier of a century ago was a remarkable place. The frontier condition brought about a "leveling of rank, a democratic equalization hitherto approached... shattering the conservative notions more or less prevalent. Gay and lesbian westerners responded to a multitude of external and internal conditions that allowed them to alternately discover or redefine their emotional and sexual desire.

Jim Wilke is former curator of technology with the Autry Museum of Western Heritage. He studies Western and railroad history and is currently working on a book about Gay Western Heritage.

A Bullrider's View in Less Than Six Seconds

By Phil Julian

I THOUGHT I COULD do it. I still might could, but I'm not sure now. I'll never be sure again. In any case, all that's left is the telling of it.

When the rodeo came to town last year, I figured I would try it again. I'd had some small successes before, on horseback in high school and on steers in a previous rodeo. But I wanted to ride a bull. And no, I won't tell you why. I can't. You might as well ask me who God is up close and personal. The answer would be very much in the same vein, and I'd do the same stuttering. Someone else can tell you about it all day long, but until your own guts speak it, you still won't get it. It is a heart thing. That's the best I can do. So, when I am asked, I say "you know, my head doesn't understand it any better than you do, but my heart understands it perfectly." And it does.

I can tell you, though, what it was like.

IT WAS JUNE 4, 1994, the second day of the rodeo. On my first day, I tied for second place in steer riding, but rode the bull for only about four seconds-no score, no buzzer, but also no injury, and only some generalized soreness from landing on a bony butt.

So on the second day, I spent the entire morning nearly unable to breathe, pacing the stands, checking the line-up sheets, quietly holding my partner's hand when I could sit still. My lungs seemed to be filling up more and more, like when you stick your head out of the car window and it becomes difficult to exhale. And when it came time for me to go, I kissed my partner fully on the mouth, looked into his eyes, kissed him again. I walked away and climbed over the high fence into the area behind the chutes.

Though still green as they get, I went through the preparations somewhat solemnly, and felt my mouth becoming dry with fear. I could not have spit if you paid me a thousand bucks to do so. I taped my spurs to cover the points. I tied my bull rigging to the top of the fence, took a handful of amber-colored rosin in my gloved hand and rubbed it up and down until the rope was hot and sticky. I stretched my long legs. I prayed. I smoked a cigarette. I looked at the bulls lined up in the chutes.

After what seemed like a lifetime, they called my name, and I brought them my bull rig. They wrapped it around the huge torso of a great black creature named "War Lord." I swung myself into the chute and lowered myself down slowly onto his amazing broad black back. They drew the rigging tight around my right hand. I squeezed my legs together hard and gave a swift, frozen tip of my hat to let them know to open the gate.

The rest of it takes on a quality that is hard to describe. It is dreamlike, and I viewed it with a sense of clarity that I have known only a handful of moments in my whole life. After a year I have forgotten nothing I can recall the timbre of the air, the exact texture of the dirt beneath us, the feel of the safety pins holding my rodeo number to the back of my blazing white shirt as we flew.

It is those first few seconds that I will always cherish most. On his first leap out of the chute, the bull swung hard right and danced straight out into the ring-the best move I could have hoped for. My left hand sailed away and behind me in a delicate arch, and I became a living rodeo poster. We rose up in the air and I tried to get my eyes focused on his shoulder blades. Just like the others had told me, you can tell from there where he is going next. True to their advice, the bull came crashing down and I glimpsed my clenched gloved hand in the rope moving just to the right, forced over by a black mound of muscle beneath it. I saw the delicate braid of the rope in amazing detail, and felt myself rising again on his shoulders, this time hard and to the right.

We jumped three or four more times, rising grandly, jumps full of raw power, the likes of which I have lusted after all my life. In the high cresting peak of those jumps, I occupied a place somewhere between heaven and earth, as we all do in reality, only I was truly awake to this fact in a way that defies logic or explanation. For those moments, I was better than a king. I was humbled, attached to the whims of grace and a part of Its fierce dance. I was, as I have never been before, aware of my own life and of my love for it.

When he hit me, there was a part of me that is ageless and predates my life as a human being, that said calmly, from the dark interior, "uh-oh." On the descending arc of our last jump, as we came back to earth, the bull had shortened his jump so that his feet were planted back almost in the same spot he had just left. Over the course of the last two huge leaps, I came forward on his shoulders a little bit more each time, trying to recover, riding as best I could on an almost vertical drive into the dirt. By the time I had gotten to the bottom of our last fall, the bull was on his way back up into the air, and with one deft toss of his head, slammed into my head with his own. It felt like I had been hit in the face with a broad shovel swung harder than people can swing, or perhaps a moving car. The lights went out then. And anything else I can tell you for the next few seconds I know from having watched it on videotape.

When I came to, I was kneeling in the dirt quite calmly, and the rodeo medic had one hand on my shoulder while he tried to pick up pieces of my teeth from the dirt in the other. There was blood all over the front of my starched white shirt. I swallowed a tooth. I could feel pieces of some of the others on my tongue. I stood up and wavered slightly; I waved my gloved hand to the crowd, and they applauded politely. I walked with some assistance, very slowly, from the ring to a medic's tent where I sat down gingerly. Someone went and brought my Davey. We declined the ambulance ride, and walked instead over to our car. He drove me to the hospital, and again, from there, I can recall almost nothing.

My jaw was broken at the hinge up by my ears on both sides. And around the front of my chin, my lower jaw was shattered into more than 15 pieces. On the underside, there was a cut requiring a few stitches. And on my left forearm, where the bull had landed his parting shot as I fell to the dirt, there was a lump the size of a healthy egg. My ring, a small silver band on my right hand that matches that of my partner's, was smashed into an oval from my grip against the rope.

I'll spare you (and me) the gory details, but it took a four-and-a-half hour surgery to put a metal plate across the front of my chin. (I woke up from surgery thinking that the man holding me in the chair was trying to suffocate me.) Six weeks later, they unwired my mouth and I began to learn to open it again, to speak, to eat. To this day, I am still missing a goodly number of teeth, but my smile, I am told, is still a pretty good one.

My partner helped me get through all of it, and yes, it hurt more than I can say. I am, and will always be, grateful to the rodeo clowns who chased the bull off of me as I sat stunned in the dirt, and to the rodeo medic who sent someone into the stands to get my Davey.

And I am grateful to the bull, too, his gift perhaps being the largest of all.

I don't mind if you don't understand it, or if you think it's nuts. But bull riding is a helluva wonderful metaphor for life itself. You hang on the best you can, and the best you can do ... the BEST you can do, is to honor the furious nature of it, its brevity and strength and incredible beauty, and to enjoy every second as if it were a lifetime. If there is such a thing as risk-free living, it certainly doesn't sound like much fun.

I will not ride a bull this year, nor probably anytime soon thereafter. But I will do other things, and some of them will be crazy as hell by conmon standards. But I will always remember fondly those few seconds when I was the rodeo poster, when the light and the sky was full in my eyes, and when I danced the cowboy dream with the best of 'em. I have not yet regretted it, not even for a second.

Forget Vampires... Interview with a Cowboy

By T.X. Enoicaras

I'm not sure if a loudmouth kid from the South Bronx (who thinks horses are what cops used to sit on at, ACTUP demos) has any business talking to cowboys or not, but that's exactly what I found myself doing on a cool California evening in early March. You know, when I left New York for good, I figured life for a boy from the Big Apple would probably be significantly different out here on the West Coast, but interviewing cowboys is something even I never expected. ("Only in California ... ," my Mom would say right about now, giggling, rolling her eyes towards the heavens, and shaking her head from side to side).

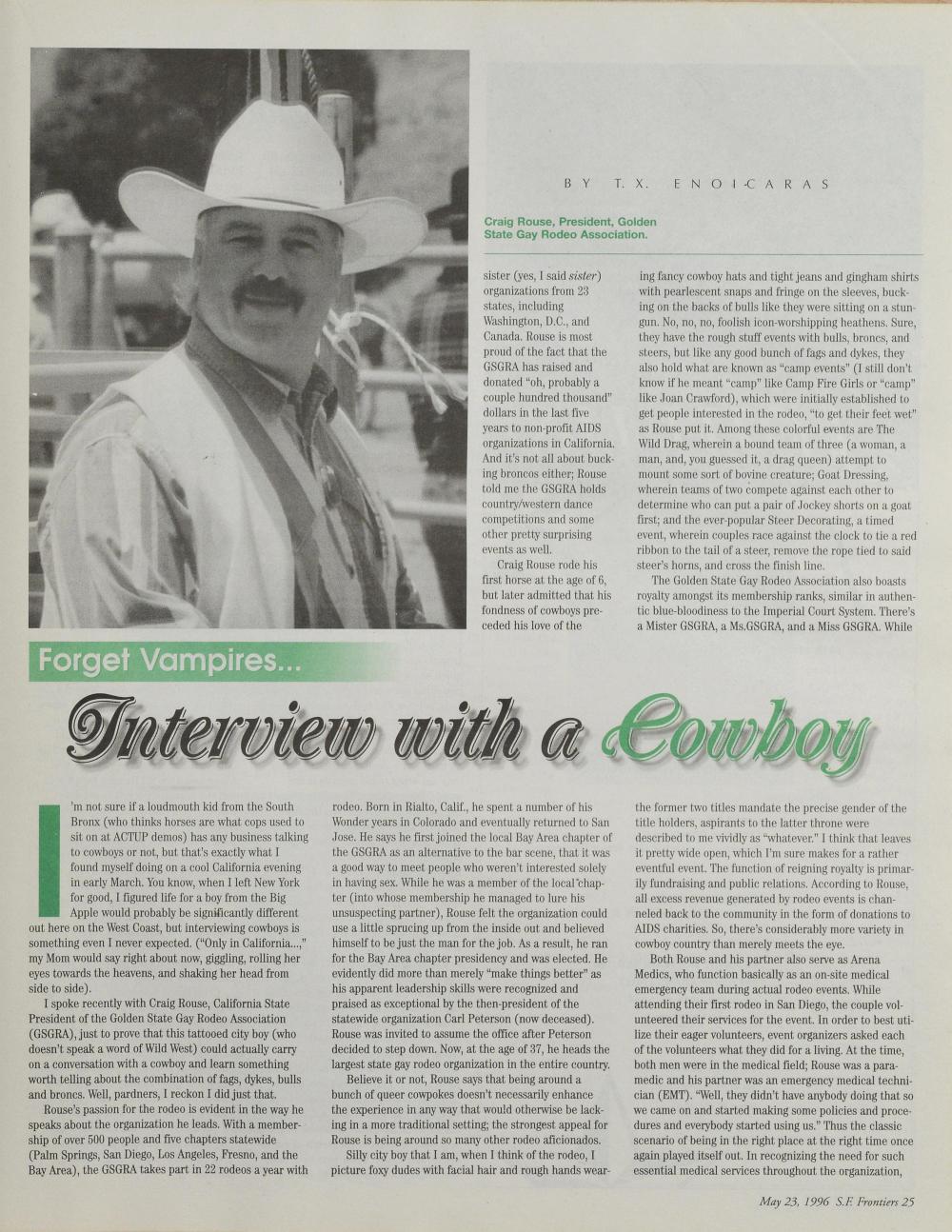

I spoke recently with Craig Rouse, California State President of the Golden State Gay Rodeo Association (GSGRA), just to prove that this tattooed city boy (who doesn't speak a word of Wild West) could actually carry on a conversation with a cowboy and learn something worth telling about the combination of fags, dykes, bulls and broncs. Well, pardners, I reckon I did just that.

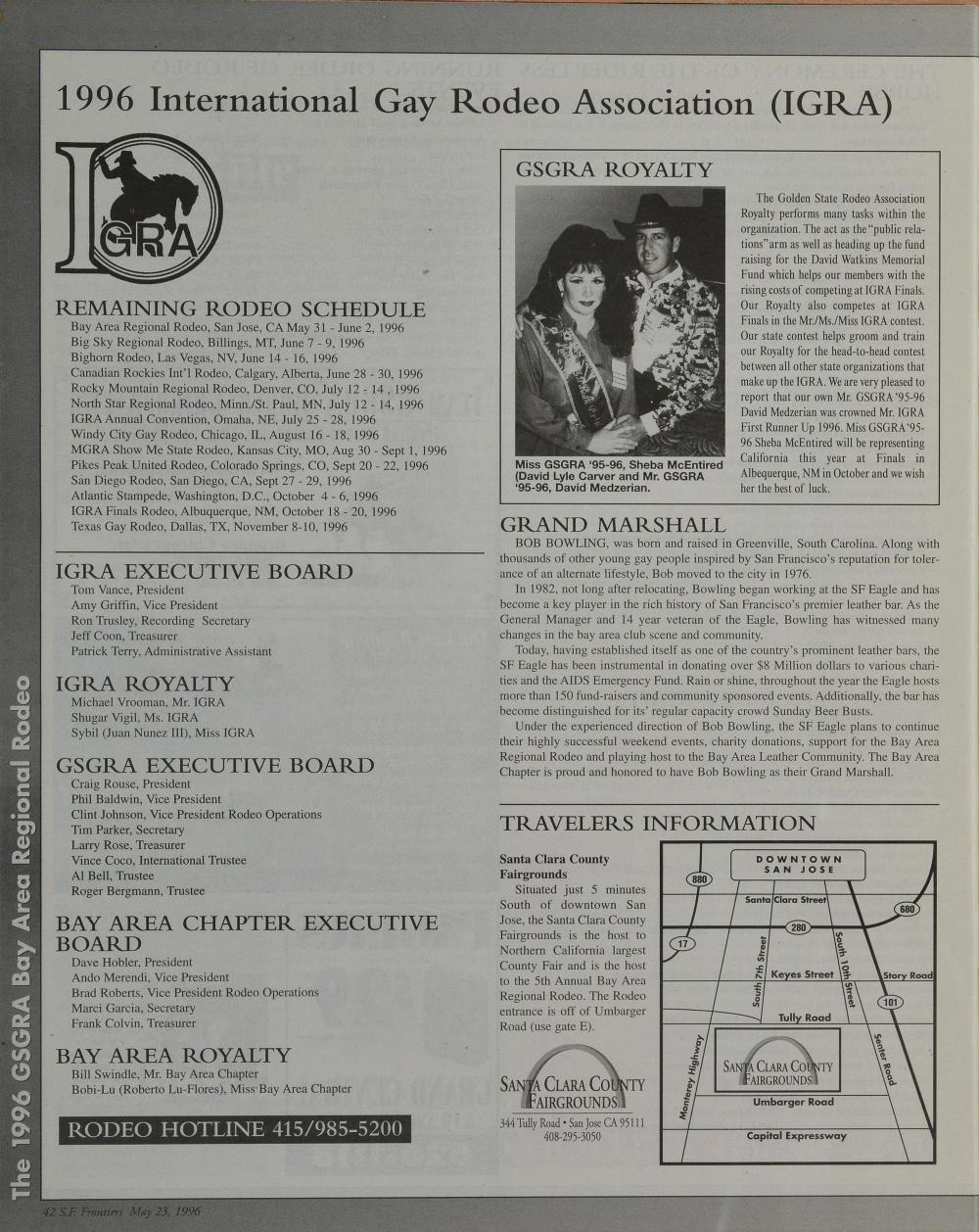

Rouse's passion for the rodeo is evident in the way he speaks about the organization he leads. With a membership of over 500 people and five chapters statewide (Palm Springs, San Diego, Los Angeles, Fresno, and the Bay Area), the GSGRA takes part in 22 rodeos a year with sister (yes, I said sister) organizations from 23 states, including Washington, D.C., and Canada. Rouse is most proud of the faet that the GSGRA has raised and donated "oh, probably a couple hundred thousand" dollars in the last five years to non-profit AIDS organizations in California. And it's not all about, bucking broncos either; Rouse told me the GSGRA holds country/western dance competitions and some other pretty surprising events as well.

Craig Rouse rode his first horse at the age of 6, but later admitted that his fondness of cowboys preceded his love of the rodeo. Born in Rialto, Calif. he spent a number of his Wonder years in Colorado and eventually returned to San Jose. He says he first joined the local Bay Area chapter of the GSGRA as an alternative to the bar scene, that it was a good way to meet people who weren't interested solely in having sex. While he was a member of the local chapter (into whose membership he managed to lure his unsuspecting partner), Rouse felt the organization could use a little sprucing up from the inside out and believed himself to be just the man for the job. As a result, he ran for the Bay Area chapter presidency and was elected. He evidently did more than merely "make things better" as his apparent leadership skills were recognized and praised as exceptional by the then-president of the statewide organization Carl Peterson (now deceased). Rouse was invited to assume the office after Peterson decided to step down. Now, at the age of 37, he heads the largest state gay rodeo organization in the entire country.

Believe it or not, Rouse says that being around a bunch of queer cowpokes doesn't necessarily enhance the experience in any way that would otherwise be lacking in a more traditional setting; the strongest appeal for Rouse is being around so many other rodeo aficionados.

Silly city boy that I am, when I think of the rodeo, I picture foxy dudes with facial hair and rough hands wearing fancy cowboy hats and tight jeans and gingham shirts with pearlescent, snaps and fringe on the sleeves, bucking on the backs of bulls like they were sitting on a stun gun. No, no, no, foolish icon-worshipping heathens. Sure, they have the rough stuff events with bulls, broncs, and steers, but like any good bunch of fags and dykes, they also ho1d what are known as "camp events" (I still don't know if he meant "camp" like Camp Fire Girls or "camp" like Joan Crawford), which were initially established to get people interested in the rodeo, "to get, their feet wet" as Rouse put it. Among these colorful events are The Wild Drag, wherein a bound team of three (a woman, a man, and, you guessed it, a drag queen) attempt, to mount some sort of bovine creature; Goat Dressing, wherein teams of two compete against each other to determine who can put a pair of Jockey shorts on a goat first,; and the ever-popular Steer Decorating, a timed event, wherein couples race against the clock to tie a red ribbon to the tail of a steer, remove the rope tied to said steer's horns, and cross the finish line.

The Golden State Gay Rodeo Association also boasts royalty amongst its me1nbership ranks, similar in authentic blue-bloodiness to the Imperial Court System. There's a Mister GSGRA, a Ms. GSGRA, and a Miss GSGRA. While the former two titles mandate the precise gender of the title holders, aspirants to the latter throne were described to me vividly as "whatever, I think that leaves it, pretty wide open, which I'm sure makes for a rather eventful event. The function of reigning royalty is prin1arily fundraising and public relations. According to Rouse, all excess revenue generated by rodeo events is channeled back to the community in the form of donations to AIDS charities. So, there's considerably more variety in cowboy country than merely meets the eye.

Both Rouse and his partner also serve as Arena Medics, who function basically as an on-site medical emergency team during actual rodeo events. While attending their first rodeo in San Diego, the couple volunteered their services for the event. In order to best utilize their eager volunteers, event organizers asked each of the volunteers what they did for a living. At the time, both men were in the medical field; Rouse was a paramedic and his partner was an emergency medical technician (EMT). "Well, they didn't have anybody doing that so we came on and started making some policies and procedures and everybody started using us. Thus the classic scenario of being in the right place at the right time once again played itself out. In recognizing the need for such essential medical services throughout the organization, as well as the obvious lack of people to fill it, Rouse cleverly employed the tried and true find-a-need-and-fill-it approach to success, and he and his partner eventually became the arena medics ... to die for.

Being the troublemaker that I can sometimes be, I broached the potentially sore subject of our wild western animal friends and how they might be feeling during all of this hootin' and hollerin'. I asked Rouse (who, by the by, is not a vegetarian which I guess means he'd eat what he'd ride) if he thought the rodeo treats its animals in an ethical manner. Without hesitation, he answered in the affirmative, quickly adding that he sits on the GSGRA Animal Concerns Con1mittee, a group which has set forth more than 75 different guidelines governing the treatment of animals, policies which were later adopted by the International Gay Rodeo Association (IGRA). "We started the committee here in California and then IGRA followed suit. Actually, our anin1als are treated better than any other rodeo animals in the world," Rouse claims. Though he clearly believes the GSGRA is doing the right thing vis-a-vis the bulls, broncs, steers, goats, horses and various other farm fauna, he concedes that People for the Ethical Treat1nent of Animals (PETA) would probably not agree with his assessment. "They judge our rodeo based on rodeos they see in the headlines, i.e. mostly Mexican rodeos, and they for sure mistreat their anin1als. And if they had gone to a rodeo two or three years ago in the Professional Cowboys Association, there too the anin1als were mistreated. I think they [PETA] always tie us in together."

According to Rouse, PETA's main objection to the treatment of animals in the rodeo is the calf-roping event.

Traditionally, cowboys on horseback chase a presumably petrified calf around the arena in an attempt to toss a rope around its tender young neck and yank it collapsing on all fours to the ground, all to the approving thunder of thousands of enthusiastic spectators. Rouse says such tasteless displays are eschewed by the Gay Rodeo Association here in California. PETA's other primary objection is to the use of spurs and electric cattle prods (you know, I used to work in a bar where one of those babies would have come in mighty handy). Again, Rouse said the GSGRA does none of that. And I believe him.

Alright, enough western lore, let's get down to the deep dish, cowboys and cowgirls. Rouse told me there are "tons" of really hot young guys who belong to the GSGRA (because I asked), and after I learned the age range of members is roughly 18 to 40, I suddenly became struck with the inexplicable urge to don chaps that weren't black and put just a pinch of something between my teeth and gums. I don't know why exactly, I just expected gay rodeo cowboys to be older but hell, what do I know? Rouse says that five or so years ago, the age range would have been a little broader but there has been an increasingly younger influx of hot rodeo dudes and dudettes into the organization. I don't know about y'all, but this is sounding better to me all the time. Alas, mine is a narrow vision because Rouse says the organization is about 50/50 men and women (and one can only assume that would include the camp event dragsters and the radiant reigning rodeo royalty). A new friend asked me if I thought boys would join the organization just to get dates. I replied, "In a heartbeat!" but I asked Rouse what he thought about it. He said most people did it for fun first, then they tried to get dates. (Balderdash!" sayeth I. I know riding a bull isn't exactly like catching a cab downtown on Manhattan's Seventh Avenue on a rainy Friday night but you've got to admit they're not all that dissimilar. I'm sure I'd find myself near the front of the line for getting fixed up with a cowboy if ever such a line formed.) Like Romeo Void say, never say never.

Craig Rouse is indeed a credit to his organization. If nothing else, he talks a mean public relations streak. To pique my interest in the rodeo, trust me, you've got to be doing something right. I mean, this man has me actually considering attending one of these country functions. Who knows, maybe there's a "bull" out there waiting for me to ride him, or vice versa (if I'm lucky). After all, like Rouse says, "We're not just a bunch of people just running around doing nothing!" Giddyup, pardner.